Canada’s GHG Emissions Reality

Canada agreed to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 30% under the Paris Agreement [1]. While many other developed countries pledged similar reductions, achieving the target is tougher for Canada.

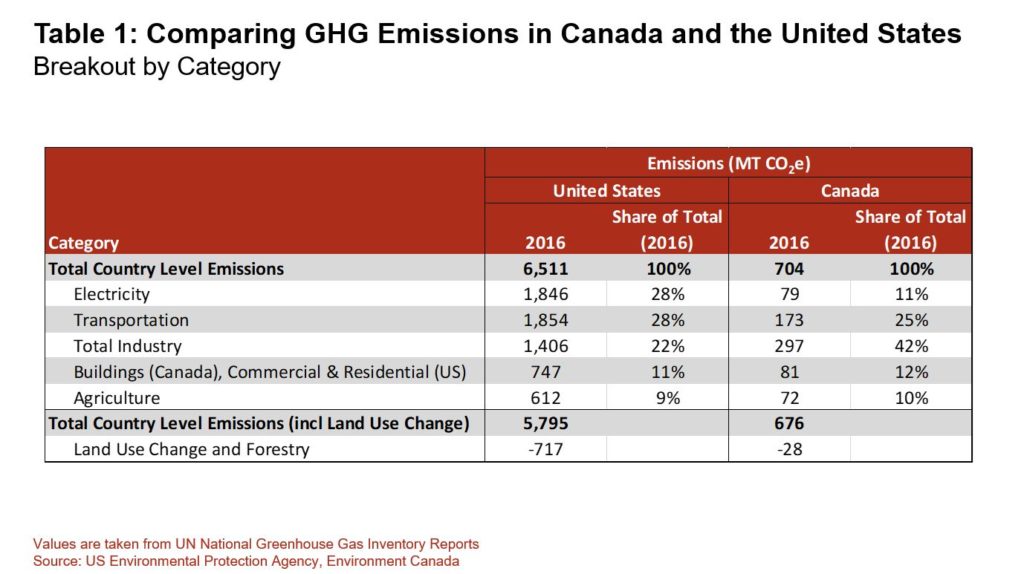

The United States has announced that it plans to quit the Paris Agreement, although it has yet to do so officially. Regardless of the US decision, it is still instructive to compare the make-up of Canadian and American emissions. The comparison demonstrates Canada’s unique challenges for reducing GHG emissions (see Table 1).

The first observation is that the United States emits almost nine times more emissions on an absolute basis (including land use). This is not surprising considering the US economy and population are roughly ten times larger.

Another difference is the amount of GHG emissions from power generation. Electricity is 11% of Canada’s total compared with 28% for the United States. Canada’s low share of electricity emissions is because the power grid is already green. About 80% of Canadian electrons come from non-emitting sources including hydro, nuclear and renewables. In contrast, 30% of US generation is fueled by high carbon coal and 34% is from natural gas. If the US could transform their power system into Canada’s current mix, this alone would achieve most of their Paris target. In contrast, even if Canada could transition to all carbon-free power, this represents less than half of Canada’s Paris reduction pledge.

Industrial emissions are another difference between the neighbours. Industry makes-up 42% of Canada’s total compared with 22% in the United States. Industrial emissions include a broad set of activities from manufacturing to resource extraction. In Canada, 60 percent of all industrial emissions come from the oil and gas sector. Canada’s oil sands emissions have been growing as a result of increasing production levels. However, innovation combined with new policies are reducing the industry’s carbon intensity. The two most recent oil sands mining projects, Suncor Energy Inc. operated Fort Hills and Imperial Oil Ltd.’s Kearl both produce diluted bitumen blends with emission profiles that are in the range of an average barrel of crude oil refined in the United States [2]. Methane leakage from the conventional oil and gas fields is also being reduced. These trends are expected to flatten out industrial emissions.

Another potential opportunity for reducing industrial emissions is getting credits for GHG emission benefits beyond Canada’s borders. For example, when Canada exports LNG to China the gas replaces coal for generating electricity. The environmental benefits from this coal to natural gas substitution are significant. The LNG Canada project alone would displace 60 to 90 million tonnes of emissions in China annually[3]. At the higher side of the range, this reduction is about half of the amount needed for Canada to achieve its Paris goal. The UN Climate Framework does consider the potential for these type of international credits, in a section still under negotiation called Article 6.

The offset given for land use change and forestry also differs between Canada and the United States. The offset accounts for the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed by the land and trees relative to a historical baseline. Canada’s offset is 25 times smaller than the American one. Canada’s northern forests are slower growing, with large unmanaged areas, and recently have been subject to large devastating insect infestations and forest fires. However, considering the size and forest cover of Canada and the magnitude of the US offset, it seems there could be an opportunity for nature-based solutions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and increase carbon storage. There is a growing recognition that forests and other land management efforts, including conserving land and planting trees can all make a difference. Yale360 recently published a report stating “[trees] are our most powerful weapon in the fight against climate change.” They quoted a study which found that planting 1.2 trillion trees would store ten years of carbon emissions[4], however climate change also poses risks for forests because fire, drought, disease and insects can release carbon.

As a percentage of the total, the other sources of emissions are similar between the US and Canada. Agriculture, transportation and buildings combined are nearly half of all emissions for both countries. The Canadian government expects the Pan-Canadian framework policies, including the carbon tax, will reduce greenhouse gases for these sectors. While efficiency gains are likely, large scale reductions by substituting hydrocarbons are difficult in the 2030 time frame. Just consider that electric vehicles are only 2% of new car sales in Canada and that half the energy consumed by Canadian households is from natural gas and changing is expensive.

The reality is that emission reductions by 2030 are not easy because of Canada’s unique situation, an already clean power grid and a large industrial sector. Still, there could be some opportunities if Canada could apply nature and international credits for making cuts.

For a more in-depth discussion on GHG Emissions, and Canada’s challenges and opportunities, tune into the ARC Energy Ideas Podcast “The Big Question: How to Cut Carbon Emissions?”.

[1] Compared to a 2005 baseline.

[2] Source: Suncor May, 2018 Investor Presentation, “[Fort Hills GHG emissions are] in line with the average crude oil refined in the United States” page 23 http://www.suncor.com/investor-centre# . Imperial website “Kearl is able to produce blended bitumen with about the same life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions as many other crude oils refined in the United States” http://www.imperialoil.ca/en-ca/company/operations/oil-sands/kearl

[3] At full build out, with both phases. https://vancouversun.com/sponsored/news-sponsored/lng-canadas-export-terminal-will-enable-coal-reliant-customer-nations-to-reduce-ghg-emisssions

[4] https://e360.yale.edu/digest/planting-1-2-trillion-trees-could-cancel-out-a-decade-of-co2-emissions-scientists-find