Commentary – Trans Mountain Flashback Reminds us to Think Globally

Canadian pipeline debates keep raging. Nothing is new. We’ve been arguing the cursed things, both oil and natural gas, for 60-odd years.

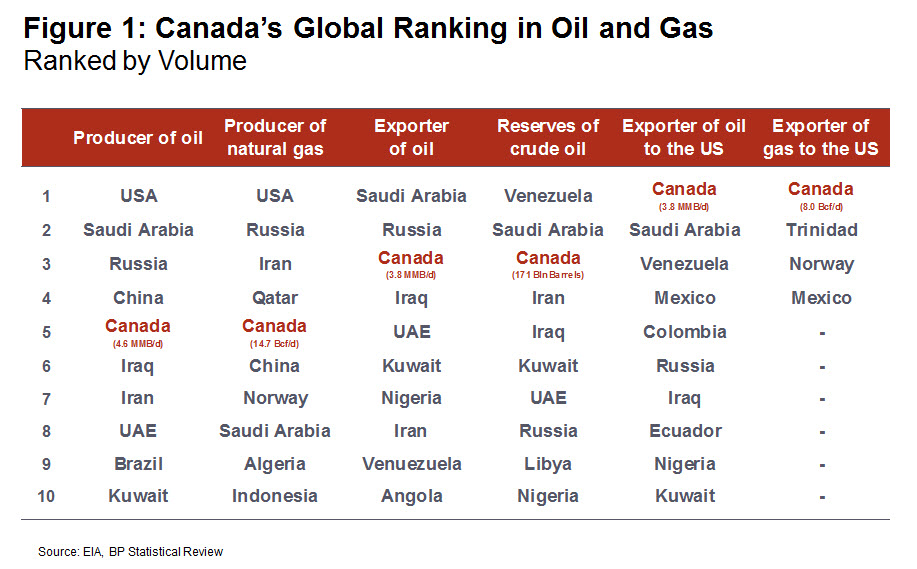

Political polarizers from past decades include the TransCanada Mainline (1954); Edmonton-Montreal Pipeline (1957); Mackenzie Valley Pipeline (1974); Northern Gateway (2005); and Energy East (2013) to name a few. Despite the antipathy, the hold-ups, the bans, and the intermittent bottlenecks, Canada has grown to be the fifth largest oil and gas producer in the world. And if you take out undemocratic, state-controlled actors we’re number two.

Volume is only one calculus. There are better gauges of leadership in today’s unsettled world. Measured against any list, the Canadian oil and gas industry is setting the pace in carbon policy, environmental compliance, safety standards, indigenous collaboration, innovation, transparency, corporate governance, social responsibility and business competitiveness too.

Volume is only one calculus. There are better gauges of leadership in today’s unsettled world. Measured against any list, the Canadian oil and gas industry is setting the pace in carbon policy, environmental compliance, safety standards, indigenous collaboration, innovation, transparency, corporate governance, social responsibility and business competitiveness too.

That statement may rankle many in the country who question one or more claims. Yet what is the Canadian gauge for measurement? An inside scale with finer and finer increments placed on top of national, provincial or civic issues? Surely, the maxim “Think globally; act locally,” also suggests an assessment of our country viewed from an outside scale, measured against a yardstick of global norms.

Which brings me to the Trans Mountain Pipeline, the source of much contention these days. The sixty-five-year-old steel tube in the ground has many stories to tell. My favourite is the tale of the oil tanker Kimon.

The Kimon Saga

On a typically drizzly Vancouver day, the Kimon’s Greek captain (I’ll call him Nick) had docked uneventfully and was ready to take on its cargo: nearly 200,000 barrels of oil.

Hoses began filling the ship’s hold, drawing oil from the white storage tanks on shore. The vessels were well stocked, having been filled with crude from the Trans Mountain pipeline. As its name implies, the pipe transports oil over two mountain ranges, first the Rocky Mountains then the Cascades. It’s a 1,000 kilometre east-to-west journey from the oil fields of Alberta to the coast of British Columbia.

While the oil was loading, Captain Nick was planning the ship’s 14,000 kilometre, nearly 30-day route. He would navigate through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, out to the Pacific Ocean, down the west coast of North America to the Panama Canal. There he would cut through to the Gulf of Mexico, around Florida, up the Atlantic Coast finally pulling into the St. Lawrence Seaway to the port of Montreal.

While the oil was loading, Captain Nick was planning the ship’s 14,000 kilometre, nearly 30-day route. He would navigate through the Strait of Juan de Fuca, out to the Pacific Ocean, down the west coast of North America to the Panama Canal. There he would cut through to the Gulf of Mexico, around Florida, up the Atlantic Coast finally pulling into the St. Lawrence Seaway to the port of Montreal.

The date was Wednesday, November 21, 1973. Eastern Canada needed Alberta’s oil as soon as possible.

The Arab Oil Embargo had been on for a month and fuel supplies were running short in countries that supported Israel. Those targeted included Canada, the United States, several European countries and Japan. All were cut back. All had to fend for themselves in securing vital supplies.

Winter was setting in and fuel for heating homes, generating electricity and gassing up big Buick’s was getting lean. Shortages of oil in the western world were beginning to sow panic.

The only west-to-east, oil pipeline that delivered oil to Canada at the time was the Interprovincial Pipe Line system, but it only went as far east as Sarnia, Ontario. The Royal Commission on Energy rejected building a Edmonton – Montreal line in 1959, in large part because overseas oil—from producers like Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Iran and Iraq—was deemed plentiful, and buying from foreign sources was cheaper than building a pipe from Alberta.

Captain Nick and his crew knew the value of their ship’s cargo, but as international sailors on a Greek-registered vessel they were indifferent to Canadian politics. Their job was to get oil from Alberta to fellow Canadians in the East. Yet it was hard for Nick not to scratch his head and opine to his fellow sailors.

“How is it,” he wondered aloud, “that a country so rich in natural resources is not self-sufficient from coast-to-coast?”

“Don’t know,” shrugged Alex, the First Mate.

Finishing up his paperwork, Nick received a telegram that complicated his route planning. The Kimon would not be able to drop its cargo in Montreal. Nor would it be able to dock in any other eastern Canadian port. Cabotage rules—the statutes that prohibit foreign-owned ships from hauling cargo between two domestic ports—would not be waived, not even in this time of geopolitical crisis.

The instructions now were to dock and unload the Kimon’s oil in Portland, Maine. From there, Alberta’s oil would finally flow to Montreal via a US pipeline (though this last leg of the journey was not Nick’s concern).

After loading nearly 200,000 barrels of oil, Nick and his crew set sail on their journey. They arrived in Maine just before Christmas, 1973, though there was no time to celebrate.

By the time the oil crisis was over, six months later, the Kimon and sister ships like the Damianos, delivered 1.5 million barrels of oil per-month from Vancouver to Eastern Canada via the Panama Canal.

Epilogue—The Kimon found herself in trouble in September, 1978. Caught smuggling off the coast of Beirut, the ship and her crew were “arrested and laid up.” Her subsequent freedom was short-lived. Ensnared in geopolitical conflict, she was sunk by rockets before the end of the year.

Captain Nick’s Lessons

At first blush, the Kimon saga is a depressing indictment of Canada’s energy circumstance. Forty some years later, domestic detractors will highlight lingering deficiencies ranging from unresolved energy security; continuing foreign imports into eastern Canada; regulatory drag; and ongoing use of costly third-party transport routes and agents (for example, in the United States) to get oil and gas to market. Others can even point to the crisis of the day and say, “This is why we need to get off oil as soon as possible!”

None of these issues make a barrel half full or half empty. In other words, it’s not so simple (I’ll be addressing these issues in subsequent columns)

Despite the challenges, increasing volumes of Canadian oil and natural gas have found their way to markets over the past century, generating $C 100 billion of annual revenue and still kicking off cash flow to invest $800 million a week in this current downturn. Rounding errors are measured in millions of dollars daily; each dollar per barrel forfeited is highly consequential to the country’s national accounts.

If there is one important lesson the Kimon teaches us it’s that when there is incentive—for example a security crisis or massive price arbitrage—these vital energy products do find their way to market, whether by truck, rail, pipe, barge, tanker or all of the above. Call it necessity. Call it innovation. Call it market forces. Call it what you want. The Captain Nicks’ of the world make it happen. And they make a lot of money doing so.

Except the Captain Nicks’ are not necessarily Canadian. Why should a foreign-owned tanker and a US pipeline take unnecessary “rent” out of our valuable barrels?

The thing that should aggravate all Canadians is that the flow of energy and capital is often sub-optimal from many dimensions, including safety, environment, security and finance. Too often, billions of dollars of taxes and royalties are unnecessarily forfeited to foreign interests. It’s happening now with price discounts on heavy oils and natural gas too. As well, the eastern half of the country is becoming increasingly reliant on higher priced, non-Canadian sources of oil and natural gas. And contrary to mainstream belief, neither GHG reductions nor environmental interests are being well served by constricting Canadian hydrocarbons, either locally or globally.

Four decades after Captain Nick skirted an external blockade, Canada’s high value resources feel blockaded from the inside out. As before, transit solutions will be found, and money will be made. Yet left unchecked, those who gain from the periodic logjams will be tactical thinkers, mostly from outside, who act opportunistically to find solutions, even if they are suboptimal for the Canadian economy and environment. It’s time for Canadians to think globally and act locally.

Next column: Canada Viewed from the Outside In.