Commentary – EV Adoption Trends: Lessons from Down South

The Ontario government recently renewed their Electric Vehicle Incentive Program (EVIP). In Canada, there are three provinces, BC, Ontario and Québec that subsidize Electric Vehicle (EV) purchases for kick starting adoption. Other jurisdictions may follow.

What can we learn from five years of EV sales?

To this point Canadian statistics are scant, and frankly the numbers are de minimis to draw meaningful conclusions. American sales data since 2011 is more significant and provides some food for thought for potential EV adoption in Canada.

There are two types of EVs that plug into a power source. First are Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs) – simplistically these are the type that you plug in at night, but still have the safety net of a small gasoline tank and generator so that you don’t run out of battery charge in the middle of Manitoba (and don’t have access to a 200 km long extension cord).

On the pure end of the spectrum, Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) have no auxiliary backup. Clandestine snacking on hydrocarbons is not allowed.

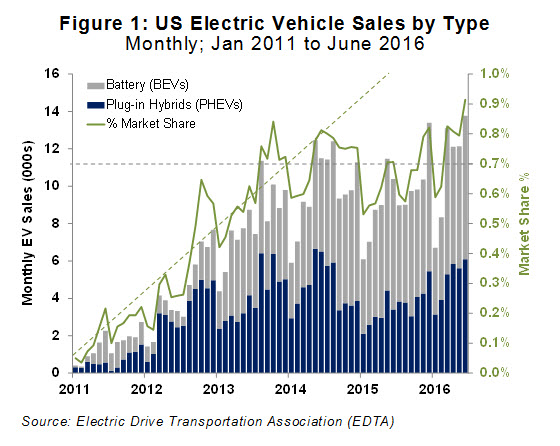

Our feature chart this week provides five years of US sales data for PHEVs and BEVs.

Embryonic adoption of EVs began in 2011, when the first serious products began to emerge. Early offerings came from notable automakers like Nissan, Toyota and Tesla. Growth was linear for two years until mid-2013. At that time collective sales reached around 8,000 per month, or not quite 0.5% of all vehicles sold in the United States. Subsidies in large-population states like California, combined with the Federal program, have helped the uptrend.

One of the most notable things in the monthly US data is the 50% drop-off in sales every January and February. Safe to say, the desire to buy electric vehicles cools off during the middle of winter.

To be fair, all other vehicle sales drop off when the blizzards are raging in Chicago and Boston. But the drop-off in gasoline vehicle sales is typically only about 25% in the first two months of the year, far less than for EVs. The US winter sales experience may suggest that adoption of EVs in northern-latitude Canada might be more challenging – at least until the negative stigma of cold-weather performance is overcome.

After the initial uptrend, combined PHEV and BEV sales since 2013 have been largely flat. This is due to plenty of reasons including: A narrow range of model offerings that limits choice; high cost of EVs versus their relative utility (even after subsidies); and low gasoline prices that lure buyers back to the status quo.

There are signs that US EV sales in the last few months may be nudging up again, mostly on the back of rising PHEV sales. But the total sold is still less than 0.9% of all US light duty vehicles, which is inconsequential to gasoline demand.

Ontario’s target of 5% of new car sales by 2020 is ambitious and will require a meaningful improvement in the factors that have stalled adoption in the US (as mentioned earlier). Issues hindering EV adoption should ease, but generous subsidies will certainly be needed in the early days.

Over the next few years more EV models are on the way from automakers like GM, VW, Porsche and Hyundai. Newer generations will offer better technology that should help mitigate buyer anxieties like range and cold weather operation. But engineering savvy won’t be enough. Future adoption of EVs will be less a function of technology and more dependent on softer factors like consumer preference in the face of competition. EVs have many advantages, but there are a lot of piston-headed people who will be difficult to convert.

Diazepam, first marketed as Valium, is a drug from the benzodiazepine family that acts as an anxiolytic. It is commonly used to treat a number of conditions, including anxiety, seizures, alcohol withdrawal syndrome, benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome, muscle spasms, insomnia, and restless legs syndrome.

The Chevy Bolt, a pure BEV from GM, will be released later this year and will be an important market test in the sub-$US 30,000 category. And of course there is the much touted Tesla Model 3, which has reported an impressive 373,000 in orders (as of May). But orders are not final sales, so the Model 3 numbers won’t be tacked onto the bar charts until the sleek cars show up in driveways – probably nothing meaningful to add until 2018.

Step changes to the petroleum dominated transportation paradigm are happening, but it’s quite likely that the overall adoption rate of EVs will remain muted, and unlikely to return to linear growth before 2018 or 2019. That’s an interesting time frame: A couple-of-years-out is when today’s lack of investment into the global oil complex is likely to show up as serious supply tightening. Rising oil prices will be the best catalyst for recharging EV adoption.

Ironically, EV-friendly Ontario and oil-producing Alberta may both achieve their goals.