If the US Slapped Tariffs on Oil Imports, Consumers and Refiners Would Feel the Sting

Around the world, people are staying home to avoid spreading the COVID-19 virus. The unprecedented human lockdown has collapsed oil demand and is causing financial distress for oil producers. The situation is particularly severe in North America, where jobs are being lost and companies are going bust. It may still get worse.

As a solution, political leaders in the United States and Canada are threatening to slap tariffs on foreign oil. This past weekend President Trump said he could impose ‘very substantial tariffs’ to protect the domestic energy industry. Alberta’s Premier Kenney also supports continental tariffs, raising concerns about ‘predatory dumping’ of crude oil by Saudi Arabia into North America.

Why impose tariffs on oil imports? One reason is to even the score with Saudi Arabia, Russia and other OPEC producers for starting a price war that is ravaging North American producers. A parallel rationale is to protect the viability of domestic oil and gas companies by increasing the local demand for their products.

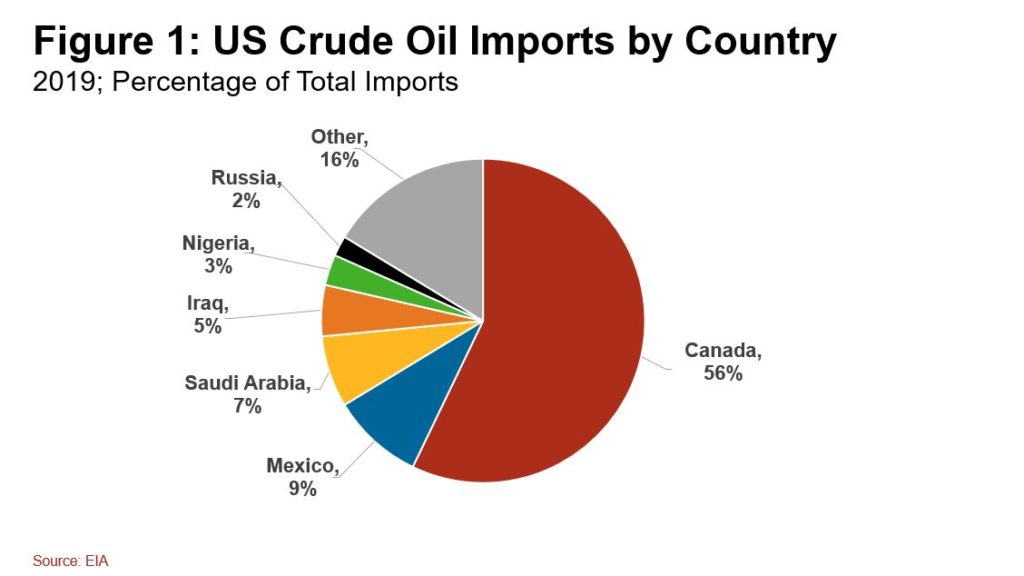

The United States is currently the world’s largest oil producer, yet they still import significant volumes of oil (see Figure 1 for top US importers). One reason is quality issues. Just like coffee beans, crude oils come in different grades and types. Some discriminating coffee drinkers will only drink coffee from Tim Hortons while others only from Starbucks. American refineries are equally picky, only consuming specific crude oils that are suited for their unique equipment and configurations. This is why the light oils from oilfields of Texas, Oklahoma and North Dakota are not adequate substitutes for foreign imports.

Transportation logistics are another reason why US refiners prefer imported oil. For example, there are no pipelines connecting the oilfields in Texas to the refineries in California and Washington State. Sending tankers through the Panama Canal should be an option, however the Jones Act – a rule that requires ships traveling between US ports to be built and operated by US citizens – makes ocean deliveries prohibitively expensive. Crude-by-rail from Texas to the West Coast is another option, but it also has high shipping costs.

As a large supplier and a close trading partner, Canada is not expected to be targeted by US tariffs. Canadian heavy oil is a vital feedstock for Midwest and US Gulf Coast refiners. Canadian heavy oil is at the opposite side of the spectrum from the light oils produced in Texas and North Dakota. Canada also supplies synthetic crude oils to US refiners that have qualities unlike any other oil.

Beyond quality, there are other insurmountable logistical barriers to replacing Canadian supply. Midwest refiners are pipeline-connected to Alberta and cannot access equivalent volumes of oil from other places. If Midwest refiners were unable to import oil from Canada, they would be starved. A lack of feedstock would force them to cut back their refinery operations, likely even deeper than what demand loss from COVID-19 is causing.

If the goal of the trade tariffs is to retaliate against Saudi Arabia, Russia and other OPEC countries for starting a price war, this plan may have some effect. The United States imports a considerable amount from the OPEC Plus group, totalling over 1.2 million barrels a day in 2019. The largest suppliers were Saudi Arabia (500,000 B/d), Iraq (330,000 B/d), and Nigeria (186,000 B/d). Russia supplied only 130,000 B/d to the Americans.

Saudi and Iraqi imports are predominantly medium oils, mostly delivered into the West Coast and the US Gulf Coast. Russia delivers medium and light sour grades to the same regions. Even though the United States produces some medium oil from Alaska and the offshore Gulf of Mexico, US production is not nearly enough to replace the volumes supplied by the OPEC Plus group.

Nigeria mostly supplies light oil to the East Coast. This possibly could be replaced by US domestic production, however hydraulically fractured US light, tight oil is disadvantaged by the Jones Act in reaching the East Coast economically.

Since the US cannot replace the vast majority of OPEC Plus imports with domestic oil, the tariffs would result in oil from Saudi, Iraq and Russia to be swapped for imports from other offshore producers, countries that are not targeted by tariffs. In many cases, these crude oil replacements would be less ideal for American refiners, forcing them to consume an inadequate, less economic crude oil diet. With US demand down sharply from COVID-19, this may not be a big deal now. However, longer term as demand rebounds it would hamper American refiners and undesirably raise the cost of fuels to consumers.

So while erecting continental trade barriers for oil would send a message to the OPEC-Plus group, it comes at a cost. There is little benefit for American upstream oil industry, and the policy harms US refiners and consumers.