Issues That Are Weighing on Oil and Gas Investment

We hear it often. Investment in Canada’s oil and gas industry has dried up over the past couple of years.

It’s true.

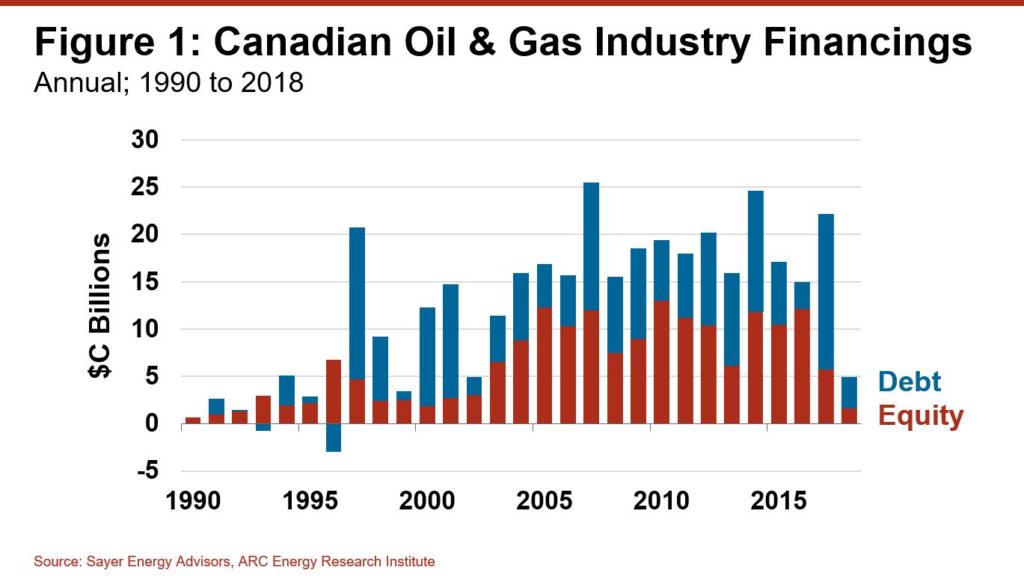

And the contraction is steep. It’s been like losing some of Canada’s largest infrastructure projects overnight. For example, the multi-year Muskrat Falls hydro project in Newfoundland and Labrador is ticketed at $13 billion. That amount of investor capital—$15 to $20 billion—has been the norm for Western Canada, every year since 2004. Since last year, it’s evaporated.

In 2018, debt and equity investment into Canada’s upstream oil and gas industry shrivelled to $5 billion according to Sayer Energy Advisors, the lowest level since 1999 (see Figure 1). This year the till may not even ring.

What’s going on? Is it Bill C69? Lack of pipelines? Commodity price differentials? Regulatory overload? To be sure these are megaphone issues with adverse consequence. And domestic geopolitics, social divisiveness, policy angst and electoral uncertainty scare away investors faster than Freddie Krueger.

But that’s not all. Other factors are contributing to a dearth of financings and capital market liquidity. Slaying Freddie in the oil and gas business is a challenge that transcends Canada. Here are the issues:

The financier’s carbon tax – Large institutional investors like pension funds are putting stringent “ESG” (Environmental, Social and Governance) principles into their investing criteria. Some have entire teams policing compliance. Many big funds won’t put money into companies unless they demonstrate mitigation of carbon emissions below a threshold. Some are jettisoning their oil and gas investments altogether to bring down portfolio emissions. This ESG trend is gaining momentum, is not unique to Canada, and puts a defacto carbon tax on the industry’s cost of new capital.

Peak oil has peaked – For decades, wide gyrations in oil and gas prices have been an investor’s friend, delivering “beta” returns. Market anxiety about where new supply will come from has shifted to nonchalance about producing too much with new technology, especially in the US. This notion of low-cost abundance has yet to be proven, but the perception is sufficient to reduce investor appetite.

Years of treatment of anxiety came difficult on me. Nothing helped much, so I was constantly looking for more effective medication. When I found out about Xanax by , I ordered it immediately. The drug turned out to be as effective as I was told. It helped me overcome the disease. Anxiety has reduced significantly, I sleep well, and I’m happy now.

Investing closer to home – American investors used to provide well over half of new funds into Canada. In less than a decade the United States has turned from needing Canada’s oil and gas to becoming its competitor. It’s not that Canadian plays aren’t viable, but American capital is reluctant to stray from home when there are plenty of new alternatives in Texas, North Dakota and Pennsylvania.

The grass is greener on the other side – When it comes to making money, it’s all relative. The money-making potential of energy as an “asset class” is compared with everything else, from real estate to cannabis. For five years there has been more money to be made in other economic sectors with lower risk. For now, the grass remains greener elsewhere and green is where the money goes.

Show me the money – Oil and gas has had a poor track record of generating long-term returns on capital. The money has historically been made in the ups and downs of commodity prices, and in rolling out more and more barrels. Now, investors have shifted their expectations from growth in price and production volumes to growth in profitability. The latter is forthcoming, but not yet established with a track record.

The EV effect – The standard anti-oil narrative is that electric vehicles are going to push the demand for oil off the Rogers Pass. Even though replacing the petroleum powered fleet will takes decades, many investors are hedging the possibility of demise by raising their risk threshold. Perceptions about imminent demand destruction are sufficient to make them more cautious about investing.

I, Robot – Ever tried selling something to a robot? Don’t bother. It’s too busy calculating profitability trends and doesn’t like to make friends. Not long ago company executives went to financial capitals like New York, London and Toronto to schmooze with human portfolio managers. Half of them are gone now, ceding their offices to algorithms. It’s tough to pitch an equity financing to a motherboard. And if you get on the wrong side of one, your performance isn’t relegated to flash memory; it lingers like a bad social media post.

For the moment, new investment into oil and gas companies is dry pretty much everywhere, not just Canada. Between 2016 and 2018, American oil and gas financings were also down over 75%. Yet nothing is static. Investor sentiment will change toward companies that overcome the challenges.

In fact, progressive factions in the industry are starting to respond to the investors’ check list. The edict is clear: Produce a better (lower carbon) product; show you can consistently make money for humans and algorithms; make more money than others; progressively lower costs with technology; and give investors their money back quickly.

That check list now holds in every industry, not just oil and gas.