Light at the End of the Pipeline

Western Canada has the cheapest oil prices in the world. Canadian heavy oil is selling for $US 45 under WTI, light oil is selling for $US 25/B less. The price markdowns are costing the Canadian economy over $C 100 million each day.

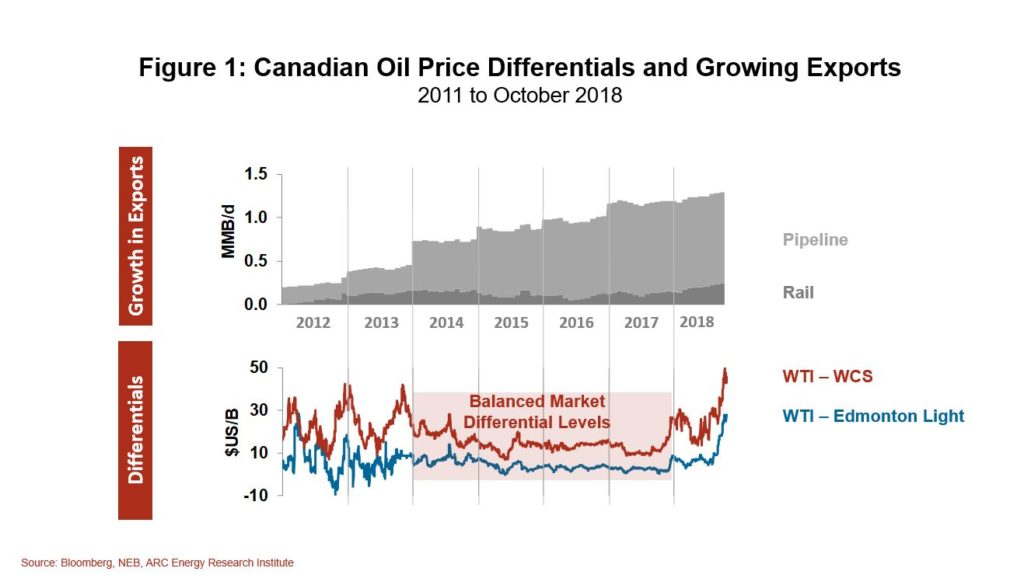

This is not the first episode of Canadian cheap oil. Remember 2012 and 2013? Back then, Alberta’s Premier blamed the “bitumen bubble” for cutting deeply into the provinces bottom line. Zealous entrepreneurs however, saw the problem as an opportunity. They started loading the discounted barrels on railcars destined for higher priced markets. The situation also triggered unexpected changes in the Enbridge Mainline. Between 2012 and 2017, Enbridge debottlenecked and changed their operations adding almost 1 MMB/d of throughput. As a result of more pipe and rail export capacity, the supply and demand balanced within two years. The volatility and size of the price differentials was flattened (see Figure 1).

For the next four years, between 2014 and 2017, the market was balanced and differentials traded at normalized levels. But now the “bitumen bubble” is back, flooding Alberta’s oil market. The recent surge in production is mostly the result of investment decisions made long ago, the last of the projects sanctioned with $US 100/B oil.

By our estimates, when pipeline and rail capacity are factored in, Canada’s oil market is currently oversupplied by about 200,000 B/d. The excess production is filling Alberta’s storage tanks and putting downward pressure on price. While it is painful now, just like in 2012 and 2013, the market should eventually achieve balance. Here are some of the forces that will act to narrow the price discounts:

- Potential oil sands production reductions. Oil sands output reached 3.1 MMB/d in August, an all-time record. However, this high output level does not seem sustainable in today’s weak price environment. Just consider the economics for producing Western Canadian Select (WCS). WCS is a blend of 70 percent oil sands bitumen and 30 percent condensate. To make WCS, an oil sands producer must first purchase condensate to mix with their extra heavy bitumen. But at today’s price, the condensate is costing almost as much as the barrel of WCS sells for. This leaves no money for paying their other production expenses, including operating and transportation costs. As one heavy oil sands producer recently told me, “we are losing money with every barrel we produce.”When you consider the challenging economics and the relatively small level of oversupply ̶ equal to about 5 percent of all heavy oil exports ̶ there seems to be incentive for producers to curtail production enough to balance the market.

- Crude-by-rail volumes are increasing. In August (the most recent NEB data), Western Canadian crude-by-rail hit an all-time high at 230,000 B/d. Crude-by-rail is expected to continue growing, potentially reaching 300,000 B/d by year end.

- Midwest refinery restarts. Refiners stretching from Illinois to Oklahoma consume over 2 MMB/d of Canadian oil, half of all supply. This past autumn, a quarter of the region’s refining capacity was temporarily offline for seasonal maintenance. These refineries are scheduled to restart in November, increasing the demand for Canadian oil.

- A heavy oil shortage. The world’s largest heavy oil refining center is not far from Alberta, on the US Gulf Coast. The region typically consumes over 2 MMB/d of heavy oil. While Alberta oil is deeply discounted, refiners in Texas and Louisiana are paying up for heavy barrels because of a drop in Venezuelan supply. Mexican Maya is currently priced at over $US 70/B, compared to $US 25/B for a similar barrel of Alberta heavy oil. The low Alberta price does not seem sustainable when the pull from the US Gulf Coast is considered.

- New pipeline capacity within a year? The long term fix for Western Canada oil markets is more pipeline capacity. The first of three projects is the Enbridge Line 3 replacement. The new pipeline is scheduled to start-up in the second half of 2019, adding 370,000 B/d of capacity. While Line 3 is not large enough to completely remove the need for rail shipments, it greatly reduces the amount of crude-by-rail rail required and should help balance the market. Beyond that, the Keystone XL and the Trans Mountain Expansion projects could be in-service by 2021. All together, these three projects would add 1.8 MMB/d of additional pipeline, enough to meet supply growth well beyond the next decade.

While the domestic pricing situation appears dark now, there is light at the end of the pipeline for Canadian producers. More demand from Midwest refineries, increasing crude-by-rail and the possibility of less oil sands production could narrow differentials in the next quarter or two. Within a year, the Enbridge Line 3 project should create another positive step change. While it does take some time, market forces always work to iron out price distortions. The bigger the distortion, the greater the force—and incentive—to bring prices back to normal.