Meet the New Boom, Different from the Last Boom

The price of oil ‘has legs’, as they say.

Running bulls are calling for another era of $100-plus. The last time we saw that number flicker on a quote screen was July 2014.

Today’s market feels more like circa 2007. Robust oil and gas consumption tugs against reluctant production; geopolitical tensions—think Russia, Ukraine, Middle East—act as a dark, phantom force to the upside.

The here-and-now price of a barrel has topped $US 80 (WTI), which is a milestone. Any price with an ‘8’ in front of it goes beyond psychological curiosity—fiscal consequences ensue outside the current $50 to $70 comfort zone.

Over the past decade we’ve seen a huge build out in renewable energy sources and great progress in pushing electric vehicles (EVs) off assembly lines. Yet despite the forces of substitution, divestment, and the persistent pandemic, 100 million barrels of oil are still flowing through the veins of the global economy.

Worldwide oil consumption will peak and roll over. But many acknowledge that day is still several years away. Meaningful decline is unlikely until the 2030s.

Not all oil is equal, there are many grades produced in the world. But the back-of-the-tablet calculation is simple: Every $10-a-barrel increase is another billion dollars a day changing hands—going mostly into the pockets of resource owners, operators, and their investors. Adding to the jingle are strong natural gas prices too.

Escalating oil and gas prices are of major consequence to Canada. Western provinces and Newfoundland and Labrador are the prime beneficiaries. Alberta dominates the share of output, with roughly 80% of all Canadian production.

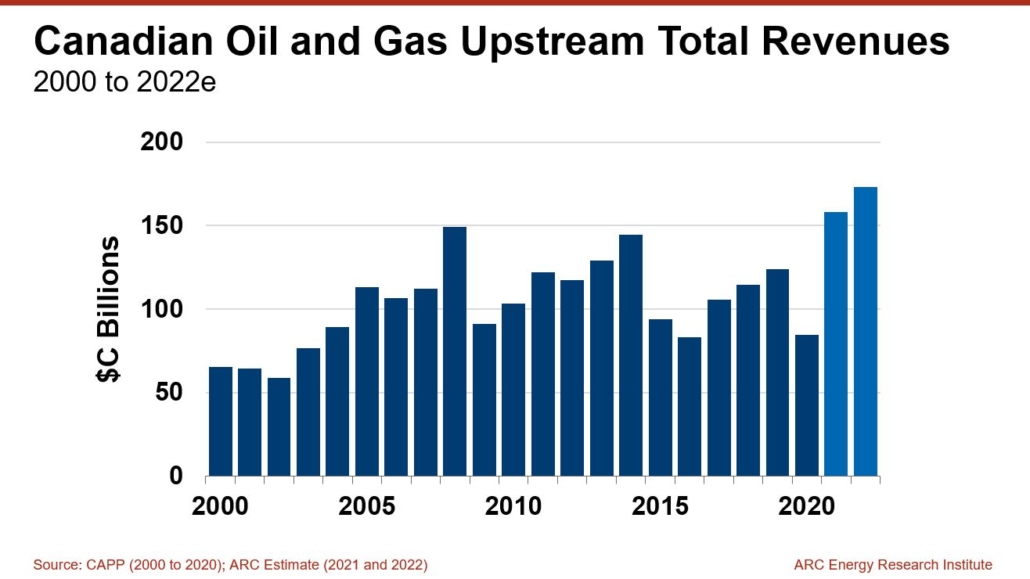

The torque to higher oil and gas prices is staggering. Last year, 2021, as commodity prices rose from the dead, Canada’s industry generated an estimated record $C 158 billion of revenue. Previously, the high-water mark was $C 149 billion in 2008. If oil price (WTI) averages a base case of $US 73-a-barrel this year, the annual Canadian sales bar could climb to $173 billion.

Yet, this isn’t a replay of the last oil bull run, circa 2007 to 2009. Nor is it the same as the post-financial-crisis 2011 to 2014 period, when robust oil prices produced industry revenues between $110 and $145 billion.

Here’s what’s different this time, with implications:

Higher output – Combined oil and gas production has grown 35% since 2007, mostly on the back of the oil sands expansion era between 2012 and 2019. Canada now produces about 8 million barrels-of-oil-equivalent per day, the fourth largest hydrocarbon jurisdiction in the world after Russia, Saudi Arabia and the United States.

Implication: Higher production volume expands top-line revenue, increasing fiscal torque to small changes in commodity prices.

Exchange rate – The last time oil poked its head above $US 80/B, the Canadian dollar was headed toward parity. Canada’s Loonie used to be a ‘petrodollar’, highly correlated to oil price movements. Today, the Loonie treads water around 80 cents to the US dollar and is mostly deaf to the call of hydrocarbons.

Implication: If the Loonie holds around 80 cents while the price of oil goes up in US dollars, producers will realize 20% greater revenue in Canadian dollars compared to the last bull run.

Market access – It’s been a while since pipelines were dinner conversation. Problems with takeaway capacity plagued much of last decade. The years 2012 to 2014, and 2018 were acute pinch points. Since then, pipe and rail export capacity has expanded. At the same time, production growth has substantially eased. So, for now the grid of North American oil transport can take away Canada’s oil production without constraint.

Implication: Higher and more stable revenue. Canadian oil prices now reflect unconstrained differentials, unlike the prior decade characterized by volatility and periods of steep discounts.

Lower costs – Nothing sharpens the commercial mind more than thin margins. Persistently low commodity prices over the past half-dozen years, combined with pressure to reduce carbon emissions through efficiency gains, have prompted hydrocarbon producers to significantly lower their costs.

Implication: Higher revenue and lower costs is yielding greater profitability.

Greater cash flow – Cash flow is the first line measure of profitability. Last year was a big year at an estimated $C 89 billion as compared to the previous high of $92 billion in 2008. This year, industry cash flow could top $100 billion for the first time.

Implication: There are many implications. Faster royalty payouts from Alberta’s oil sands projects are notable. In the depths of the pandemic total royalties, across all provinces, were less than $C 4 billion. In 2021, their treasuries grew to over $12 billion. This year, Canadian oil and gas royalties could top $18 billion.

Shareholders are the big beneficiaries of free cash flow in this bull run. Dividends and share buybacks are attracting investors seeking cash returns, driving equity prices higher. Much of the shareholder base has turned over, because of ESG and divestment pressures.

Less investment – Historically, North American oil and gas companies invested all of their cash flow back into the ground, drilling to add more reserves and boost production. Since circa 2018, investment into output growth has required permission from investors. The new crop of shareholders has spoken: more cash, less oil and gas.

Implications: Less investment diminishes the ability of free-market oil suppliers to respond to demand for petroleum products, reinforcing expectations of higher prices. Lower capital expenditures by the industry also means producers are more cash taxable, which adds to government coffers, both federal and provincial. However, less drilling also means that the spending in the rural economies, where the oil and gas fields are located, is not nearly as strong as has been in past high oil price eras.

Repatriation of influence – Perhaps the greatest change between the last bull run and now is the structure of the industry. The buyout of foreign multinational interests—for example Statoil, Chevron, Murphy Oil, Marathon Oil, Devon, Shell, Husky and ConocoPhillips—by Canadian corporations has repatriated decision-making power around these assets into downtown Calgary. Suncor, Cenovus and Canadian Natural are now the big beneficiaries of these acquisitions. Retrospectively, the foreign multinationals financed much of the oil sands expansion between 2000 and 2015, then sold the projects at losses to domestic operators.

Implications: Cash flow generated by the Canadian oil and gas industry, especially from the oil sands, is more contained. In other words, profits being generated from local resources won’t be sent out the back door to foreign head offices.

This bull run of oil and gas prices is very different in character and scale from those in the past. On the supply side, it’s a massive reversal of fortune for the oil and gas industry in Canada and every producing jurisdiction abroad.

One thing hasn’t changed: As in past eras, escalating oil and gas prices will tilt the fiscal balance between producers and consumers. The ensuing inflation will challenge notions about energy security, affordability and transition.

And the price of oil is not even at a $100-a-barrel.