Commentary – Not 1986

A replica of the Back to the Future DeLorean is shown at the Cars of the Hollywood Screen car show. Source: www.dreamstime.com © ecadphoto

The headlines say that we have seen this kind of collapse before. With the benchmark US oil price (WTI) nearing the $US 40/B floorboard, wide spread pessimism is taking root with a growing number of voices associating this downturn with the sickly era circa 1986.

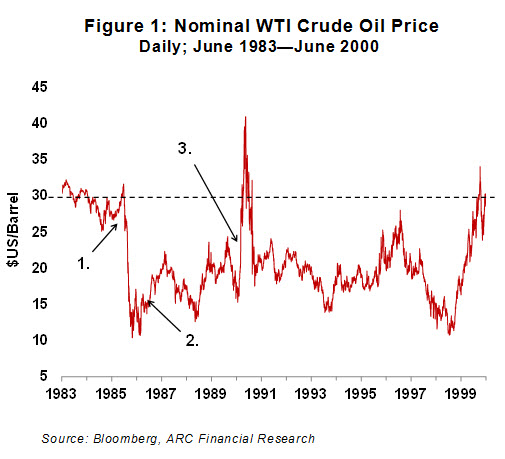

The downturn of the mid 1980s was certainly grim. With the exception of a short-lived price spike when Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990 (see Figure 1, point 3), it took about fifteen years for the price of oil to recover to its pre-1986-crash levels.

Although oversupply was the initial catalyst of both 1986 and current price crashes, with OPEC actions center stage in both cases, there are many differences between 1986 and today. The 1986 crash and the resulting decade and a half of low prices that followed was the result of a truly massive oil oversupply, unlike the situation we are now facing.

To understand the differences between the two events, let’s rewind the clock back to the 1970s. In response to the 1973 oil price shock, oil importing countries implemented legislation aimed at reducing demand. Over the next decade, the use of crude oil for electrical generation was substituted out by coal and nuclear power, and conservation measures were put in place to help reduce consumption.

Between 1979 and 1985, a weak economy and new government mandates reduced global oil demand by 5 MMB/d. At that time, OPEC’s policy was to hold the oil price near $US 30/B (almost $70/B in 2015 real dollars). To maintain this price in the face of declining demand, OPEC was forced to ratchet down their oil production by 14 MMB/d. Saudi Arabia bore a large part of the burden and their production dropped from near 10 MMB/d in 1979 to 3.6 MMB/d in 1985. At the same time, the artificially high oil price caused non-OPEC supply to surge; production from the UK’s North Sea took off, the Alaska North Slope grew, and Mexican oil production almost doubled.

When Saudi Arabia’s oil minister, Ali al-Naimi commented this past December on the “crooked logic” that a low cost producer keeps oil price high enough to support growing production from higher cost competitors, the situation of the early 1980s was likely front of mind. During the 1980s, al-Naimi was the president of Saudi Aramco, and he saw firsthand the dangers of ceding too much market share.

By December 1985, OPEC production levels were unsustainably low. Over the six year period, OPEC’s market share had dropped from 46% to 29%. Cutting more production was no longer an option and OPEC members decided to switch from a policy of focusing on price to one dedicated to regaining market share (see Figure 1, point 1). In the next year, OPEC’s average production increased by over 2 MMB/d. This higher production level was still only a fraction of OPECs full potential, and spare capacity at the time was pegged at over 12 MMB/d. Considering that the world consumed 61 MMB/d of crude oil back then, the spare capacity was equal to 20% of global demand.

By the end of 1986, OPEC members tried to boost oil price by making a collective cut of over 1 MMB/d (see Figure 1, point 2). But by that point, the level of oversupply was well beyond what OPEC could control. Frustrating the pace of the recovery were the newly commissioned non-OPEC projects, including those in the North Sea and Alaska that could expand their production at a low cost.

Let’s compare the 1986 situation to 2015. Using the latest figures from the IEA, OPEC spare capacity now sits at 2.2 MMB/d, and even when you add the 1.8 MMB/d of crude oil that is being produced above current demand levels, the amount of “spare oil” is at most 4 MMB/d or 4% of global demand. Compare this to 20% in 1986. If it took fifteen years to sort out a 20% oversupply, assuming that all else is equal, a mere 4% glut should take far less time

Of course, not everything is equal, some things are better. Today’s non-OPEC production sources are not as amiable to low cost expansion as in 1986. Tight oil declines quickly and needs constant investment. Expanding oil sands or deep water is not economic at current prices; and, even assuming a markdown in the cost for building new projects, it is tough to imagine how they could become profitable at today’s oil price.

And some things are the same; notably the law of supply and demand still holds. Low price stimulates more consumption. Even though conservation efforts reduced demand in the early 1980s, between 1986 and 2000 cheap oil spurred consumption to grow by 2% per year. The IEA now expects oil demand to grow by 1.7% this year, more than two times last year’s pace.

This is not a 1986 rerun. With the exception of OPEC’s policy curveball, by many measures the situation is not as dire today (although it feels like it). Even without a wildcard such as a major supply outage (from a civil war or a terror attack for example) or a voluntary cut by OPEC, robust growth in global oil demand along with an inevitable slowdown in global supply growth should conspire to strengthen prices much faster than 1986.