Commentary – What Does Oil Price Recovery Look Like?

Source: www.Dreamstime.com © Wenbin Yu

By now, we’ve all received the memo on distress in the oil and gas industry.

Daily, depressing blogs, news stories and twitter feeds are diarizing the corporate carnage, project cancellations, idle oilfield activity and 100,000-plus layoffs. The cash drought is so severe, even the line-ups at Tim Hortons have subsided. That’s what happens when $50 billion of investment is sucked out of an economy in 18 months.

But enough negativity. Let’s look ahead to sunnier days.

What will the memo say when oil prices recover? What will happen when positive cash flow and investment starts trickling again?

Flashback: The last time commodity prices recovered after a crash was back in 2010, following the Financial Crisis. A barrel of oil rebounded from $35 to $80 in a little over a year. For the most part, Humpty Dumpty was put back together again and the business of oil and gas resumed investing in traditional upstream projects – big offshore platforms, oil sands projects, large conventional fields and budding tight oil plays.

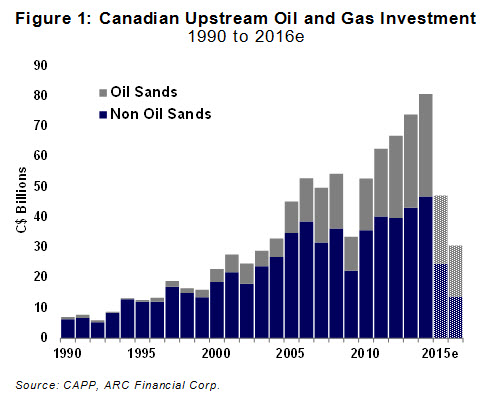

In Canada, recovering upstream cash flow with access to easy debt and equity, begat a quick return to spending by companies. By 2011, total capital expenditures pushed through a record $62 billion, almost double the 2009 dip. Tens of thousands were employed and hiring qualified people became a big-league sport; industry wages began rising faster than any salary cap could contain. Rising stakes stoked the pace of Canadian investment, which peaked in 2014 at $80 billion-a-year – 42% to oil sands and 58% to non- oil sands. (Figure 1)

Five years ago China and the developing world were expected to consume a hockey stick trajectory of never-ending energy. So big projects, small projects, quick projects, slow long-term projects, oil, natural gas, and oil sands projects – however hydrocarbon development was sliced and diced – all segments were beneficiaries of the 2010-to-2014 Klondike-style rush to build out productive capacity.

But don’t expect a replay going forward. Oil prices are anxious to go up again and they eventually will. But this “recovery” will play out differently.

Even if prices firm up in the latter half of this year, the ensuing ramp up in activity will be slow. Much fiscal damage has been done by the current drought of capital.

Meaningful cash will start to trickle back into the system once oil prices pop above $50/B again. But the money won’t be going back into the ground – the first dollars will be headed to bank vaults, placating bruised bankers who pushed out too many loans. Next, producing companies will have to take time to restock their wallets and heal their balance sheets. The result: investment, activity and employment momentum will lag oil price recovery by many months, well into 2017.

Yet it could take even longer. The industry also has to build up the nerve to risk investing billions of dollars again. Today, the outlook for energy is more uncertain than in 2010. Consumption patterns are changing. Substitute systems are emerging. Environmental concerns are mounting. Who knows what we’ll be driving and how much oil we’ll be consuming in five, ten or twenty years? It’s all very unsettled.

One way to deal with the risks of the unknown is to shorten the amount of time that capital is exposed. “Long term” used to be 20 years. Now the patience level to take risks and earn a return has been reduced to less than 10 years. And it’s probably going to go to five.

Tweeting out capital in short chunks sounds good in principal, but reducing investment time horizons is inconsistent with traditional oil and gas development. Over the last 50 years the industry has migrated to massive scale – big mega-projects that are designed to pay out over decades. But small is the new big, and short is the new long, so the legacy investing model has changed its rhythm.

Big global projects that have been cancelled or delayed – like 17 of them in the oil sands region – are unlikely to be resurrected on a price rebound. Even if oil prices pass through $80/B, there will be hesitation to invest in multi-decade projects again. Notwithstanding the threat of substitutes, above ground risks have increased in oil producing jurisdictions around the world. Here in North America it’s the threat of changing government policy. Elsewhere it’s the perils of risks like corruption, civil war, and expropriation.

Unlike the last recovery, tomorrow’s returning investment dollars won’t be spent across the full spectrum of oil projects. Prudent, selective, cautious and impatient; these new adjectives will be used to describe “short cycle” investing. The first meaningful dollars will go back into North American tight oil plays in the US and Canada, where capital can be minimally exposed before returns are realized. In Canada, this means that the spending split between oil sands and non-oil sands will shift significantly to the latter, as it was up to the mid-2000s.

Memo to file: When oil investment returns, hundreds of billions of dollars will be concentrated on a narrower set of plays, projects, companies and jurisdictions. Humpty Dumpty will be put together again – lopsided.