Commentary – Bearish Oil is Not Our Cup of Tea

Here’s a contrarian thought for discussion: The Brexit drama is actually bullish for oil prices.

The next time you go for afternoon tea, tell your friends that the anxiety surrounding Britain leaving the European Union is likely to strengthen arguments for higher oil prices, not weaken them.

I’ve just received my package from https://dietitianlavleen.com/where-to-get-ativan/ and wanted to say thank you. Your customer service is an absolute top. The support service specialists were really kind and patient to explain the details I wanted to know. Thanks to them, I managed to buy the brand medication I needed with the price lower than elsewhere. My 10 out of 10 for you!

But that’s not what others around the table believe. Common thinking around last week’s toodle-oo vote is that Europe’s pain is going to start a trend toward shredding trade agreements, de-globalizing commerce and radiating economic malaise around the world. Ergo society at large will be using less oil, further weakening the price.

That’s not all. Reinforcing bearish Brexit beliefs is the idea that filling up gasoline tanks will slow down, because currency markets are fleeing to the safety of the US dollar, raising the value of the greenback, and making barrels more expensive to buy in countries with devalued money.

Those are two good arguments worthy of a cup of Darjeeling.

I wouldn’t debate that annulling free-flowing trade agreements will cause the gears of commerce to grind a few basis points off global GDP. But to what extent do changes in broad economic activity impact worldwide oil use?

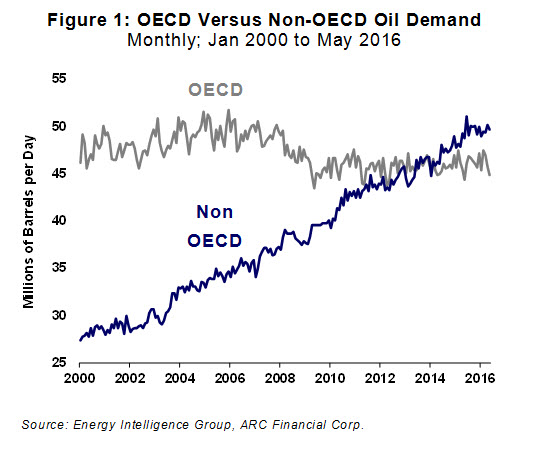

Not much in Europe. For countries like Germany, France, Italy and the UK there hasn’t been any correlation between oil and economic growth for at least 10 years. Even in other developed, “western” countries like the United States, Japan and Canada there is little causality between a bureaucrat publishing GDP numbers and a citizen filling up their SUV. For the past 10 years on average, net oil consumption has been mostly flat to declining in the elite club of the 28 wealthy countries that make up the OECD, or Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (or non-cooperation as the current mood suggests).

Admittedly, in big emerging economies like China and India, there is cause-and-effect between firing up combustion engines and wealth-creating commerce. It can be shown that for every 1% of GDP growth there is a corresponding 0.5% pull for oil volumes. Yet caution is advised in acting like a horse at Ascot wearing blinders. GDP is not the only determinant of the direction and magnitude of oil consumption. Even the severity of the 2009 Financial Crisis did little to reign in consumption growth in emerging economies.

The most influential factor affecting oil consumption is price. Data from the past several months reminds us, not surprisingly, that usage goes up when price goes down. Cheap gasoline has an almost mystical allure; for example, the driving stats in the US are setting new record highs for oil demand this summer. And more than any time in history new vehicle buyers are biasing their choice to bigger gas guzzling vehicles.

For the first time in five years OECD countries, led by the US, are showing a meaningful uptrend in oil use – not because of GDP, but because of cheap gasoline.

In part due to this price effect, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has ratcheted up its 2016 and 2017 oil consumption numbers. Their current view is 1.3 MMB/d of growth this year and another 1.3 MMB/d next year. Yet the real-time monthly stats show the IEA may be overly cautious: For the first quarter of 2016, oil demand increased 1.6 MMB/d year over year. In this context, the average 2.1% rise of the US dollar against other currencies following the Brexit vote is mere noise in quelling oil demand.

The Brexit-driven bullish case for oil is more on the supply side of the oil equation. Financial markets are roiled again into uncertainty and global trade agreements are at risk. So who wants to invest big dollars under a cloud of ambiguous rules?

Before Brexit, the propensity to invest in or lend to worldwide oil projects, especially multi-billion-dollar megaprojects, was already weak due to above-ground uncertainties the size of Downton Abbey – environmental policy, geopolitics, civil unrest, price wars and transportation substitutes to name a few unknowns.

At a minimum, the fog of Brexit has just driven the oil industry’s cost of capital higher. That’s not a bearish argument for oil prices at a time when production is showing hints of declining capacity in basins around the world. A dearth of capital has always been a bullish leading indicator for oil prices.

Brexit is unlikely to affect demand growth in a meaningful way; to the contrary it’s more likely to delay investment into new supply, which will lead to higher prices. Don’t expect oil markets to price these arguments over afternoon tea. By the time price rises the waiter will be serving a stiff aperitif.