Commentary – The Other Side of the Oil Storage Story

Oil pump jacks in the Middle East.

Source: www.dreamstime.com © Typhoonski

It may come as a surprise ̶ especially considering the recent volatility in the price of oil ̶ that market fundamentals have improved in the last three months. For the first time in two years, the world market is now nearly balanced, meaning that oil consumption is almost equal to production.

Despite this positive development, between July and the beginning of August, the oil price fell by 20 percent. It has partly recovered since, mainly due to wishful speculation that OPEC might freeze their production levels.

Despite achieving near market balance, oil bears continue to bias their analysis toward record high crude oil and product storage levels. Pessimists believe that high inventories will keep a ceiling on price for the long term, fueling the well-worn, “lower for longer” view.

How should the market be thinking about the amount of stored oil the world needs to feel secure about its energy needs? And how much crude oil is stored in readily accessible facilities?

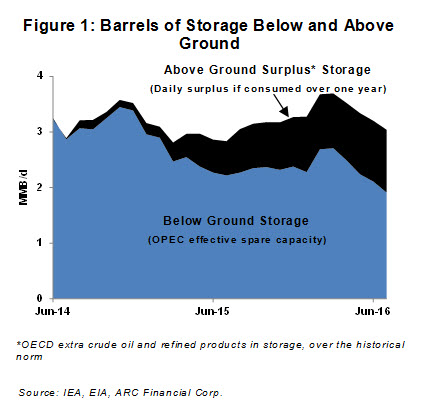

At this point, developed world commercial crude oil and product storage levels are about 400 million barrels above the historical norm. This is a large number. If 1.1 million barrels of inventory is drawn down each day, consumers would still take a full year to use up the excess oil and products.

Yet, while market watchers have been shining a spotlight on high above-ground storage levels, they are neglecting the readily accessible barrels that have been developed below ground. This is called “spare capacity,” which can be thought of as the pump jacks that sit on standby until the market is in short supply. With the turn of a few valves, spare production capacity can rapidly be ramped up to fill a void.

Saudi Arabia is the holder of nearly all the world’s spare capacity. For decades, oil markets have relied on the Kingdom to crank up production when above ground storage tanks were falling short. The need for this spare capacity was seen in the 2011 Libyan Civil War. When Libyan production dropped by over one million barrels per day, Saudi production ramped up to offset the loss. Again, in 2012, when Iranian production declined 0.6 million barrels per day from the nuclear sanctions, the Kingdom opened up the valves to supply the shortfall.

Barrels of spare capacity below ground, plus storage above ground, must be considered collectively when thinking about how much oil is available for the world to feel secure about its supplies. If the market has ample spare capacity, then arguably, storage levels can stay low and vice versa.

Think of it like this: The early pioneers stored enough food to survive the entire winter. Today, city dwellers store almost nothing. Our pantries can be instantly replenished at the corner grocery store. But if urbanites saw a credible scenario that the supermarket shelves could run dry, they would need (and want) to store more food.

This two-year price war has catapulted Saudi Arabia’s production to all time high levels, reducing the Kingdom’s spare capacity by over one million barrels. And beyond Saudi Arabia there isn’t much spare capacity in the ground. OPEC members like Nigeria, Libya and Iraq cannot ramp-up their underutilized productive capacity because of wars and terrorism. Others like Venezuela are in economic shambles.

Right now the International Energy Agency (IEA) has generously pegged OPEC’s effective spare capacity at 1.9 million barrels per day; a value that is 1.4 million barrels per day lower than a few years ago. This lost spare capacity is greater than the surplus oil in storage, if it were to be liquidated over one year (see Figure 1).

OPEC’s spare capacity is expected to drop more in 2017. The IEA expects that the group will need to pump out even more barrels in 2017, just to satisfy the world’s growing appetite for crude oil and to offset the declining market share of other oil producers.

When thinking about the on-call oil needed to serve growing consumption, the market appears to be overly biased to above-ground storage capacity. While the above-ground storage tanks are full, the below ground storage tank (OPEC spare capacity), is only half full and dropping.

OPEC’s shrinking below-ground storage suggests that true storage for managing upstream supplies is less than the market thinks. It’s another sign that market fundamentals are more bullish than they appear.