Commentary – The Market at Work

The free market always has a way of sorting out inefficiencies. Western Canada’s recent oil pipeline saga (there have been many over the past six decades) will be recorded as a classic case study in how market forces work to remedy anomalous price differentials.

The problems started around 2012. Pipelines were bumping-up against their limits for moving more crude oil out of Alberta. Compounding the trouble, customers in Ontario and the Midwest (who made-up more than 75% of Western Canada’s export market) were being over supplied due to a flood of North American crude oil. Growing output from the Canadian oil sands, along with a surge of tight oil from North Dakota and beyond was greater than what local refiners in the land-locked region could process.

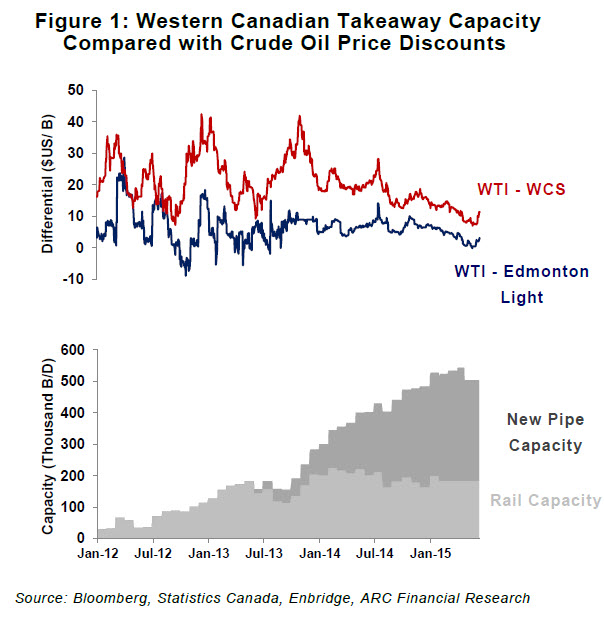

Canada’s export market was quickly becoming saturated with too much oil. Prices for all grades fell, honouring well-worn economic theory. Between 2012 and 2013, Western Canadian crude oils were typically discounted between $10 and $20/B. At times during 2012, discounts were 50% higher than that level. As a result, domestic oil producers forfeited between $15 and $20 billion in revenue per year. Low oil prices were squeezing the Alberta government’s finances too. In January 2013, then Premier Alison Redford blamed the “bitumen bubble” for the government’s budget crunch. As a result, efforts to lobby for new pipelines were intensified by both industry and government. The market would act faster than all of them.

While “market access” problems were capturing the public’s attention, the economic law of one price – the principle that a product must sell for the same price in all locations, net of transportation and other fixed factors – was already starting to iron out oil price distortions between Canada, the US and world markets. After all, the price arbitrage created by the lack of pipeline capacity was a multibillion-dollar opportunity for any enterprising organization that could find a way to move the discounted crude oil to a higher priced market.

Starting in early 2012, zealous entrepreneurs started moving crude oil by rail cars – a practice that was commonplace a hundred years ago. Once the deeply discounted crude oil was loaded into a rail tanker, it was mobile and was able to reach higher paying customers anywhere in North America, including many that were previously inaccessible by pipeline. Around that time, I met a spirited young business man who built his first prototype for loading crude oil into rail cars in his backyard. By the end of 2013, the cumulative efforts of many enthusiastic capitalists had boosted rail shipments from Western Canada to over 200,000 B/d.

Wide price differentials also triggered changes in the Enbridge Mainline. This primary artery into the US and eastern Canada currently makes-up about 65% of all of Western Canada’s export pipeline capacity. Over the last few years, Enbridge has painstakingly debottlenecked and optimized their pipeline. Surprisingly, in the first quarter of 2015, they created 340,000 B/d of additional capacity compared to a year earlier. With more tinkering and optimization, Enbridge expects that at least 100,000 B/d more takeaway capacity can be added this year. Altogether, this would be the equivalent of adding 60% of the take away capacity of the infamously delayed Keystone XL.

The economic principle of “perfect competition” has been another force at work. This rule describes the positive economic benefits that flow from having more customers. Thanks to crude by rail, Western Canada’s customer list of US refineries has been growing. Customer diversity got another boost last December with the startup of the Flanagan pipeline, that connects the Enbridge Mainline system in Illinois to Cushing, Oklahoma. This new artery has already increased deliveries of Western Canadian crude oil to the US Gulf coast by 150,000 B/d. And before the end of this year, the Line 9 reversal through Quebec will allow for more market expansion, enabling Western Canadian crude oil to be delivered via pipeline to refiners in the east of the country.

Figure 1 shows the result of all these changes on Western Canadian crude oil price. There is a direct correlation between new takeaway capacity (both rail and pipe) and the softening of price differentials for western Canadian crude oil. Not only has the average crude oil price discount been squashed to near record lows, but price volatility has dramatically decreased as well. The market works.

Behind the active debates surrounding the need for Canadian pipelines, epitomized by Keystone XL, Adam Smith’s invisible hand of the market quietly acted to restore value to Western Canadian crude oil. Although differentials are much narrower now, the importance of adding more takeaway capacity is not diminished. The market always thrives best with more competition.