Commentary – The Service Sector: Innovating Through the Downturn

Bleak metrics to describe the oil price downturn are easy to come by. For instance: the oil price is down almost fifty percent from last year, and drilling rates in Western Canada are about half of last year’s levels. However, numbers only tell part of the story. To understand how the people and businesses on the ground are adjusting, I left the tall office towers of downtown Calgary, and headed 450 km northwest of Edmonton to Grande Prairie (GP), Alberta.

Although the oil and gas industry has been part of GP’s economic fabric for decades, the recent development of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing has created a new chapter of growth in the community. To serve the booming industry, a countless number of oil field equipment yards, shops, hotels and houses have sprouted-up over the past four years. In tandem, the city’s population has grown by 25 percent, expanding to 68,556 people. This is only part of the growth, as many more people have settled in the surrounding counties and municipalities over the past few years.

Sitting down with Mayor Bill Given, I learned that the oil patch is only one of the pillars in a diverse economy. As the name suggests, the region’s large fertile plain makes it a productive farming area. Bordered by forests, there is an active lumber industry in the area. The Grande Prairie Regional College brings students to the region, and when complete, the new regional hospital and cancer center will create additional jobs in the community. GP also serves as a retail shopping hub for the communities to the north (an area with a population three times larger than the city), and across the BC border, the construction of the $9 billion Site C hydro dam will also benefit GP, since it will generate work for local residents and businesses.

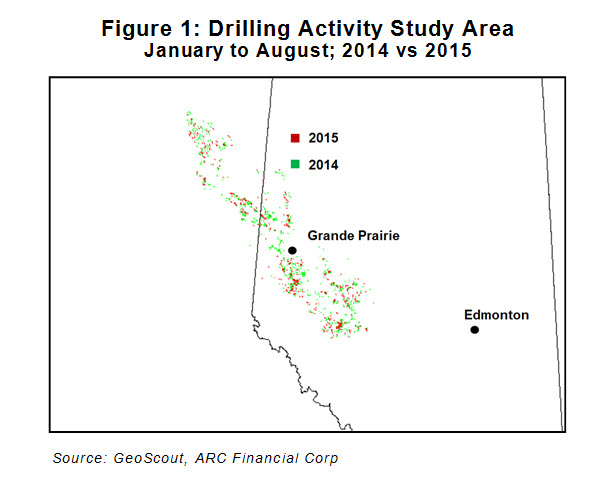

Driving around the area, symbols of the oil and gas sector downturn are hard to miss. The auction yard has a long line-up of heavy haulers, dozers, motor graders and excavators. Spared from auction (for the moment) are equipment yards filled with all types of idle machines. To quantify the impact of the recent oil price downturn on GP’s oil patch, we compared new wells drilled this year with the year before (see Figure 1 for study area). For the first eight months of 2015, we calculated a 42 percent year-on-year decline in drilling in the GP area. Although these numbers seem quite discouraging, the activity levels are actually faring better than the Western Canadian average of a 53 percent year-on-year decline in drilling.

Individual service company utilization levels vary widely from this 40 percent average. Companies who are working for operators that have maintained spending are managing to keep busier than the rest. Regardless of their utilization levels, a competitive market is forcing service companies to deeply discount their pricing. With less revenue per unit of work, corporate survival depends on finding ways to reduce costs.

Typically, labour is the largest single cost for a service provider and consequently job cuts are often the first tactic to reduce costs. Beyond this, wage roll backs are the next obvious cost cutting solution. However, many business leaders are cautious about making large reductions to employees’ salaries. One concern is the prospect of losing their best workers. Although the job market is not what it used to be, top-tier employees are still able to find work with competitors or in other sectors of the diverse GP economy. Another concern is the financial strain that can be caused by large pay cuts. This difficult situation is an unhappy lesson on the dynamics of employee pay: It’s easy to give employees a raise, but not so easy to deliver pay cuts.

Beyond lowering wages and conducting layoffs, companies are still searching for other ways to cut costs. Assuming that buyers can be found, selling equipment to reduce debt loads is another obvious method for lowering expenses. This explains the large inventory of equipment at the GP auction yard. Operational improvements are another tactic. Companies can reduce their downtime by streamlining logistics and operating practices. Capital requirements can be reduced by rationalizing inventories of equipment or by changing payment terms to suppliers.

For some companies, diversification is an option. Firms that truck goods, fix equipment, or build roads can seek work outside of the oil patch. Other businesses are shifting their focus, from providing services aimed at new gas wells and facilities, to activities focused on maintaining and optimizing existing assets.

Despite these corporate survival tactics, the double whammy of less activity and discounted pricing has taken a toll on the service industry. Still, in spite of the hardships, service firms continue to push on – replacing their growth plans with survival plans. And while they would not tell you they are thriving, for now at least, the firms that I met with are finding innovative ways to weather the downturn.