Commentary – Weathering Volatility in Natural Gas Markets

Natural gas has taken significant market share in North American energy markets, especially the United States.

Annual consumption of the robust fuel has gone from 22.0 Tcf in 2005 to 27.5 Tcf in 2015. Most of the rise has been in the past five years with low-cost shale gas pushing out policy-burdened coal, while going head-to-head with policy-enabled renewables. Natural gas now represents 29.4% of American energy needs, up from 23.0% ten years ago.

Those are interesting here-and-now factoids, but there are always consequences to major shifts in energy market share. For natural gas, the progressive gain in market share is making consumption much more sensitive to seasonal variations, especially temperature changes.

In other words, natural gas demand is now more levered than ever to variations in winter and summer weather. And that means producers and consumers should expect more volatile prices.

Energy consumption is often analyzed by breaking down usage into sectors, for example: Residential, Commercial, Power Generation, Industrial and Transportation.

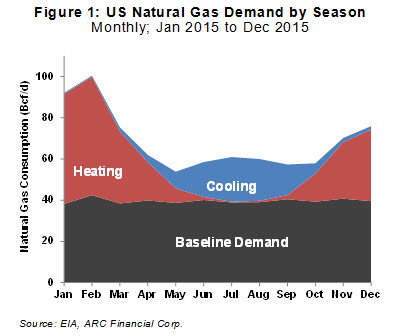

Another way of slicing and dicing where a pipeline takes a cubic foot of gas, is to break consumption into three seasonal categories: Winter Heating, Summer Cooling and Baseline or “Weather-less” demand. Our feature chart this week shows seasonal decomposition, by month, for 2015.

Baseline or “Weather-less” demand is like a thought experiment: What if the weather never changed in the United States and the temperature everywhere was 65° Fahrenheit (F) throughout the year? In such an idealistic case, natural gas consumption would not vary by turning thermostats up and down. Our chart shows that weatherless consumption averages around 40 Bcf/d, which is 58% of total consumption.

But there are weather variations. About 12% of total goes to cooling and 30% to heating.

Growth in natural gas consumption has largely come from power and industrial sectors, both of which have significant weather-related seasonality. There is also more lighting load in the darker winter months, so power demand also follows the highly predictable (thankfully) planetary cycle.

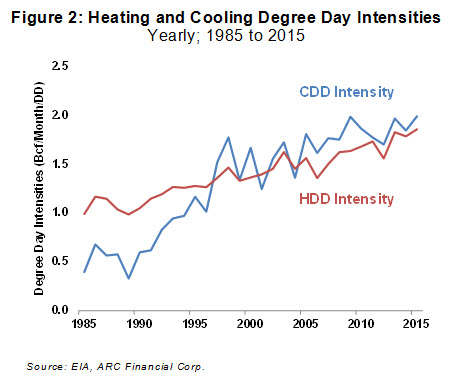

There are a number of sub-trends that fall out of greater seasonally-dependent natural gas demand. One is the rising “intensity” of each “degree-day.”

A degree-day is defined as the number of degrees that a day’s average temperature deviates above or below 65° F (18° Celsius) – the weather-less norm. An autumnal day across the US that averages 75° F racks up 10 “cooling degree days” (CDDs); conversely at 55° F the count would register 10 “heating degree days” (HDDs).

The pull for natural gas supply as a function of a one-degree change in the average temperature is increasing. Back in 2005, an additional degree day in a winter month resulted in an incremental 1.5 Bcf of consumption for that month. By 2015, the intensity was up to over 1.9 Bcf – a 30% increase in weather-related sensitivity. Our second feature chart shows the progression of CDD and HDD intensities over the past 15 years.

The simple conclusion to all this is that natural gas demand is much more sensitive to seasonal temperature variations.

A warmer than average summer is much more consequential to pulling down inventory levels than it used to be only a handful of years ago. A fact that was demonstrated this past summer, when heat waves reduced the storage glut. It’s not surprising knowing that each degree pulls on more gas than in the past.

Of course the winter converse is true: a warmer-than-normal winter is much more likely to balloon out storage facilities and clobber prices.

Daily prices at Henry Hub, the benchmark US trading post, have varied from $1.50 to over $8.00/MMBtu since January 2014. On a percentage basis, the volatility is greater than oil. Being caught at the lower end of the price range is especially hard on a producer’s cash flow; the top end hardly pleases utilities and industrial customers. Both buyers and sellers should be aware that greater degree-day intensities translate into amped up seasonal price variations.

Pundits (like me) who have followed North American gas economics over the past couple of decades know that they have to fake being a qualified weather forecaster. At a minimum, we are required to read the Farmer’s Almanac or wait for a hibernating animal like a hedgehog or a groundhog to climb out of its hole before making predictions.

More market share now means that seasonal natural gas demand is more sensitive to temperature variations, which means greater price volatility. Buy low sell high seems like good investment advice. Equally, market participants should skip watching hedgehogs and be more mindful of hedging the price of the commodity.