Commentary – Where Is All This Oil Coming From?

Source: Pixabay.com

Source: Pixabay.com

Millions of barrels of excess crude oil are weighing down tankers that are being filled from pipelines coming from fields where rows of overworked pump jacks are bobbing their heads up and down like spooked horses.

Oil markets are spooked again too.

In the absence of output restraint – a return to some sense of prudent resource management by the world’s largest state-owned producers – oil prices could submerge below the industry’s $40/B Plimsoll line for the second time this year.

It should come as no surprise that the glut is largely being produced out of the Middle East, where this mother of all price battles began over two years ago.

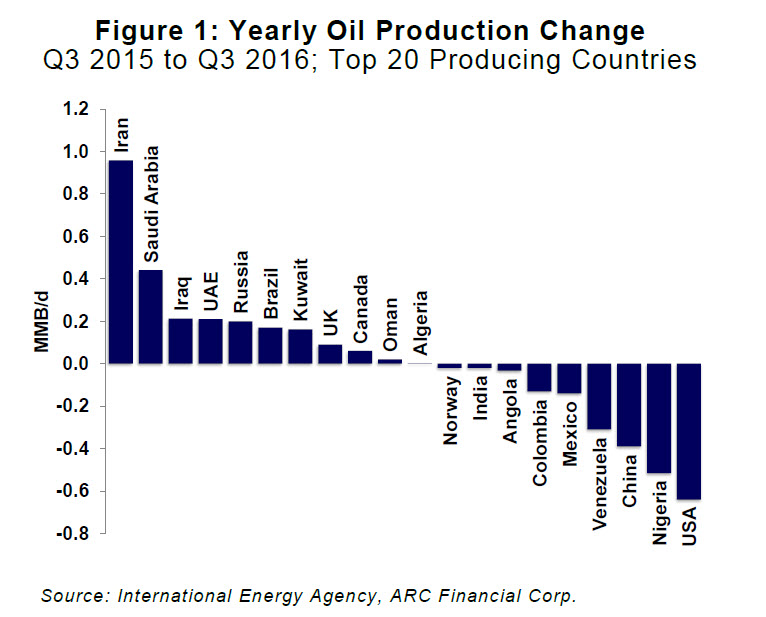

Year over year, up to the end of the third quarter of 2016, output from the oil-rich region is up by almost 2.0 MMB/day (see Figure 1). Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq have been the most aggressive about ramping up their flows. Kuwait and the UAE are also pumping more.

Russia, though not part of the region, nor a member of the OPEC cartel, seems content to over-satiate the market too. Being paid in US dollars for their oil, a half-price, sanction-laden Ruble makes the Russians quite happy to join the fray.

Then there is Libya and Nigeria. Both are unpredictable. Recent news suggests that the two appear to be cranking their valves open again. That spooks the market too – at least until the next time rebels blow up their infrastructure.

It’s not likely that oil will flow out of the ground much faster next year without greater upstream investment. But that isn’t much consolation. Left unchecked (i.e. no agreement at the next OPEC meeting) the strained volumes that are being put into white storage tanks around the world now will continue to pressure prices well beyond 2017.

By any business measure, this price war should have been over by now. But oil is not a business like airline tickets, pizzas or inkjet printers.

Many decision makers behind the world of deep holes, silver pipes and black barrels do not strategize with game theory. No spreadsheet captures geopolitics, grudges, spite, religious conflict, or survivalist instinct into the calculus of how much oil to pump out. For countries with warring regions, there isn’t any textbook notion of cost curves or break-even economics; just selling more oil at any price liberates badly needed cash.

In the absence of common business sense, the fiscal pain of this downturn is biting the entire global industry hard. Third quarter, 2016 financial results from global super majors prove the point.

The likes of ExxonMobil, Chevron, BP, et al, have disclosed again how costly this downturn has been. Cash flow among these players has been de minimis from upstream operations this year, especially in Q1 when the price of a barrel was trading below $40. Average capital spending for the group has now been slashed to almost 50% below peak 2013 levels. Production is flat to declining. Tellingly, even after two years of aggressive cost cutting, innovation and productivity improvements, the largest of these independent oil companies (IOCs) have to keep taking on more debt and selling assets to cover their coveted dividend payments.

If the best run companies in the oil world can’t make a buck and grow, which operators can? Most national oil companies (NOCs) aren’t making enough money to cover their host country’s “social costs,” which is a polite way of saying they are running up massive fiscal deficits. At the state level, the overproducers are fiscally weak too. So much so that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) recently projected that the cumulative fiscal deficit among the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), 1 Caucasus and Central Asia (CCA) 2 oil exporters, and Algeria could reach about $340 billion over the next five years.

Mega fiscal deficits, for IOCs or NOCs are not sustainable. Eventually the production volumes from every region will go into decline from lack of cash flow and re-investment. Producers like Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela and even the United States highlight that point in Figure 1. Canada appears to be growing, but that’s only because of the lagged output from prior investment.

The next OPEC meeting is scheduled for November 30th. With price in the low-to-mid-forties there is already talk of a deal again (of course!)

“No pain, no gain,” is an adage that can be applied to fighting for market share. So maybe the best thing that can happen before November 30th is for oil prices to scrape lower again to a threshold of pain that may finally motivate a deal for collective gain.

1 The GCC comprises of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

2 The CCA oil exporters comprises of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.