Commentary – $50 Doesn’t Sound Good to the Rigs of the World

Like us humans, it seems like oil markets have two ears.

Going in one ear, is the squeal of the resurgent US oil industry. In the other ear, it’s loud chatter about whether or not OPEC and friends are complying with production cuts.

In between the ears, in the minds of the traders, the price for a barrel of oil dozes between $50 and $55/B.

Occasional bullish shout outs of unrelenting consumption growth, scary geopolitics and declining production may be heard. Others growl like bears that GDP is weakening in key developing economies, there is too much oil in white storage tanks everywhere (there is) and so on, ergo price should go down. But the bull-bear din has not yet been loud enough to shake the market out of its fifty-to-fifty-five price trance.

So what in the world of oil is the noise that’s relevant beyond a walking rig in Texas and a war-damaged valve in Libya – something that really tells us about where the industry is headed (or not)?

One thing that’s drowned out in the information commotion is the rig activity in various regions beyond the US. Its time to revisit this data, which is a real-time whistle that tells us about the economic viability of drilling for more oil at $50-a-barrel worldwide.

No wonder we’re not hearing much. The sound of rising masts and grinding bits is pretty weak beyond the US and Canada.

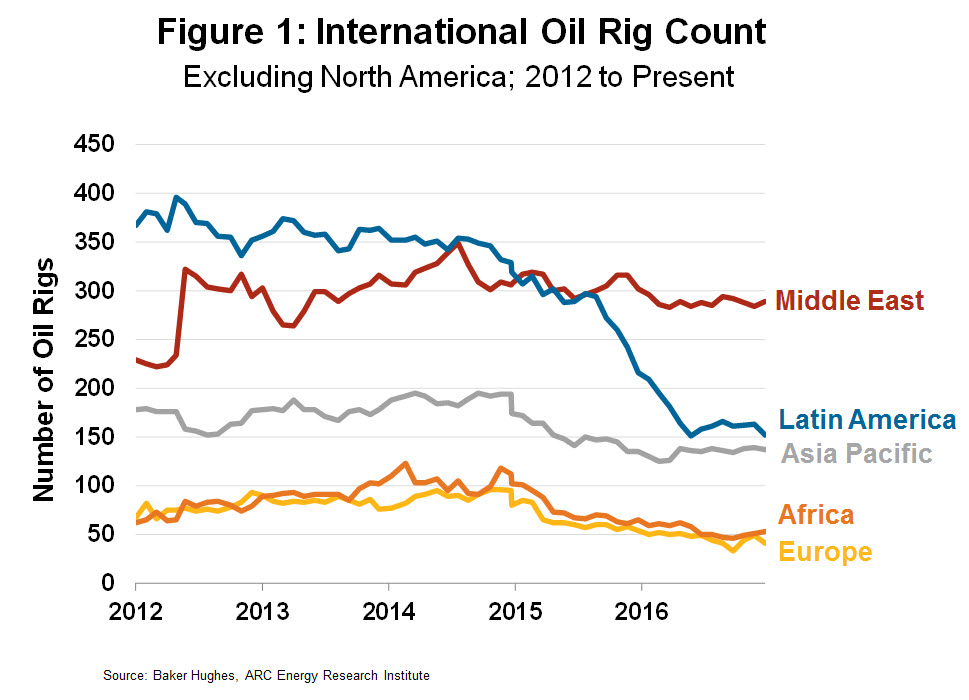

Latin American oil-targeted activity has levelled out at just over 150 rigs after dropping precipitously from a pre-crash peak of 395. The signal is pretty clear: Not much works at fifty bucks a barrel between the Rio Grande and Patagonia.

Rigs in the Asia-Pacific region have stopped falling at the 135 mark too, down from 195. Not very exciting and hard to make a case that current oil prices are enough to open corporate wallets, even after all the hoopla about declining service costs. Ditto for European and African drilling; both regional oil-targeted rig counts are holding in the 40 to 50 range with no upward inclination in the absence of higher prices per barrel.

Most interesting is the Middle East region. Drilling was active in the deserts through to the end of 2015, which contributed to the mother of all price wars in early 2016. Over the past 12 months a gentle decline in activity is noticeable, off an average 15 rigs down to the 290 mark. Capital is being husbanded in these countries, recognizing that $50 a barrel doesn’t kick off enough cash flow to warrant incremental re-investment. Stated more bluntly, state-owned oil companies don’t have a lot of extra money for drilling after the necessity of paying cash dividends to their states. (Figure 1)

Other international drilling tidbits include trends in OPEC versus non-OPEC. The 12-member cartel’s activity is down nearly 20% from 2014 levels and holding for the moment around 300. Non-OPEC activity (excluding US and Canada) is still falling but not as steeply as last year. (see Figure 2)

Other international drilling tidbits include trends in OPEC versus non-OPEC. The 12-member cartel’s activity is down nearly 20% from 2014 levels and holding for the moment around 300. Non-OPEC activity (excluding US and Canada) is still falling but not as steeply as last year. (see Figure 2)

The most notable downward trend right now is offshore drilling. Peaking at 340 oil-and-gas platforms bobbing in seas and oceans, the count has steadily fallen to 200 over the past two years. Indications are that it’s going lower, a trend that is consistent with the understanding that long-term upstream megaprojects are passé in the face of short-cycle onshore investment. So it’s no surprise that the trend on dry land is pointing up. (see Figure 3)

Yes, rig productivity has increased many-fold over the past couple of years, but that’s mostly a North American phenomenon. Such gains are the prime reason that only two places in the world where the rig counts are up meaningfully are the US (up 55%) from this time last year, and Canada (up almost 54%).

Too much oil in inventory and prolific productivity in places like Texas will continue to resonate loudly over the next several months, potentially putting downward pressure on price again. But the weak background noise of global drilling activity is a distant alarm for shortfalls in future oil supply—all in the face of still-robust year-over-year consumption growth.

So what falls on deaf ears today may be music to the market’s ears tomorrow.