The Canadian Oil & Gas Investor Perspective with Eric Nuttall

This week, our guest is Eric Nuttall, Partner and Senior Portfolio Manager at Ninepoint Partners. Eric manages the Ninepoint Energy Fund (NNRG) and the Ninepoint Energy Income Fund (NRGI).

Here are some of the questions Peter and Jackie asked Eric: How would you compare investing in Canadian oil and gas producers versus U.S. companies? Do you still believe Canada is undervalued relative to the U.S., as you did when we spoke a few years ago? With OPEC announcing on September 7, 2025, that it will add even more supply to the market, why are oil prices remaining so resilient, and what is Saudi Arabia’s strategy? What are your expectations for North American natural gas prices, particularly in Canada, which has experienced exceptionally weak pricing this year? Canada has seen a wave of consolidation in the oil patch—how do you view corporate consolidation in this context? You have long advocated for oil and gas producers to buy back shares, but if Canada succeeds in building new export pipelines for oil and gas, would you support companies growing production to create value rather than relying solely on buybacks? How can new export pipelines be built if investors continue to prefer buybacks over growth? Finally, do you believe Canadian oil and gas companies still trade at a “green discount” due to climate policies that burden the sector?

Please review our disclaimer at: https://www.arcenergyinstitute.com/disclaimer/

Check us out on social media:

X (Twitter): @arcenergyinst

LinkedIn: @ARC Energy Research Institute

Subscribe to ARC Energy Ideas Podcast

Apple Podcasts

Amazon Music

Spotify

Episode 294 transcript

Disclosure:

The information and opinions presented in this ARC Energy Ideas podcast are provided for informational purposes only and are subject to the disclaimer link in the show notes.

Announcer:

This is the ARC Energy Ideas podcast, with Peter Tertzakian and Jackie Forrest, exploring trends that influence the energy business.

Jackie Forrest:

Welcome to the ARC Energy Ideas Podcast. I’m Jackie Forrest.

Peter Tertzakian:

And I’m Peter Tertzakian. Welcome back, as always. And as always, we’re going to talk about our favorite subject, or at least among the favorite subjects of our audience, and that is investment in the stock markets, particularly the markets for oil and gas. But before we go there, talk about some of the news that we’ve seen over the course of the last week since we recorded. We’ve got the EV mandates are changing and there’s some OPEC news. What do you want to tackle first?

Jackie Forrest:

Well, let’s talk about the OPEC one. Now, OPEC is kind of surprising everyone already because there were these three tranches of supply that they were keeping off the market and they put the first tranche, which was over 2 million barrels a day, they announced they wanted that back on the market a year early, but now over the weekend they say they’re going to even add another 1.6 million barrels a day, the second of three tranches.

And most analysts don’t think all of that really exists, that there is really not all that much spare capacity in countries outside of some key ones, like Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait’s another one.

So probably not that much will come on the market, but it gets you thinking a little bit, what is Saudi’s plan here and is there a strategy change? So I think oil price is quite resilient as time of recording and actually when you think about the outlook for oil markets into the next quarter or two, it looks like there could be quite a significant oversupply. This makes it worse. Oil prices actually stayed pretty resilient in the face of that. Now there’s no inventory builds yet, so we’ll see how that happens.

But anyway, something to talk about. And then of course these EV mandates, 20% EVs by 2026 is what the automakers in Canada were supposed to deliver. Mark Carney has paused that and actually put a pause on the whole thing as they study it, which as a reminder, by 2035, a hundred percent sold in Canada, were supposed to be electric as the liberal policy was before. So I think it’s smart to revisit obviously the growth of electric cars, the rate of growth is changing, it’s slowing compared to what people thought, and I think it’s a smart move.

Peter Tertzakian:

Yeah, the rate of penetration of electric vehicles, at least on this hemisphere has slowed down, in China is still fairly strong and that has impact on the demand side. Actually the economy is the number one dictator of whether or not oil demand goes up or down, and we want to talk about that. In fact, we want to talk about that. We want to talk about the OPEC news and much more with our special guest who’s no stranger to our audience, because this is his third time back.

We are delighted that Eric Nuttall, Partner, Senior Portfolio Manager of Ninepoint Partners is back. Always a delight to have you, Eric, welcome.

Eric Nuttall:

Thank you so much. I really appreciate your podcast. It helps me many times get through heavy Toronto traffic.

Jackie Forrest:

Okay, well anything that can help with that. Well, we always listen to you too. So we’re really interested in the discussion that we’ve been following, because it has been since June of 2023 since we had you on the show, and I just thought I would recap your views there. And at that time you felt Canadian oil and gas companies were undervalued and you thought that the stock values were reflecting a lower price, 55 to $58 long term.

And with these companies having such great cash flow yields, you thought that there was a really compelling opportunity. And I went back and looked at the Canadian Stock Index, the one that kind of looks at all of the companies, the S&P, TSX Oil and Gas Index. It’s up about 15% since that time, and the US is pretty flat actually overall since that time. So Canadian stocks have come up quite a bit. So I thought I’d just kind of get your perspectives of when you think back of what’s happened since then.

Eric Nuttall:

Yeah, a lot has happened. Not much has changed from a sentiment perspective, from a valuation perspective. I’m happy that you pointed out the performance delta between Canadian and US stocks because I think it reiterates our view then and even now, that there remains a discount between Canadian energy companies and US. Less so now, without getting overly political, I think a lot of the hostilities that we experienced for 10 plus years have lessened a little. I think there’s a growing realization about some of the challenges that US shale faces from an inventory depletion perspective.

And at some point, I think in the near future, there is going to be a premium being placed on those companies and countries with long data reserves. And so from an investable perspective, Canada really, really shines well. I think the other thing that has changed the most over the past year that has really made it challenging for energy investors has been the volatility, having to deal with geopolitics.

Trump has been, I find very destabilizing from perverting people’s sense in terms of the abundance of US shale and drill, baby, drill, and demanding lower oil prices. So that’s been hurtful on sentiment. Dealing with geopolitics, which as an energy investor is not something you ever want have to deal with because it can distort supplied and demand balances and what that means for price, but having to deal with Israel and Iran and sanctions on Russia and price caps, and all of these different things.

So I think where we stand today versus back when I last joined you, energy stocks remain deeply out of favor. Sentiment remains very, very negative. Evaluations I find still very compelling, especially we think we’re… There’s caution, there’s a cause for pause right now for oil, but I am really quite optimistic about the outlook for 2026 and beyond. And now for natural gas, especially after the sell off, and especially with LNG Canada ramping other projects, the outlook for Canadian natural gas is finally positive for the first time in many, many, many years. So we remain bullish in the energy sector despite some of the short-term challenges that we face.

Peter Tertzakian:

Well, let’s drill down into some of these issues, if you pardon the pun, but I want to go back first of all to the comparison between the Canadian and the US oil and gas industry, and we want to make sure we’re comparing apples to apples or as the case may, be barrels to barrels. Can you break down the oil and gas composition? You talked about long-dated reserves, which are like the oil sands versus the other different types of producers, because we want to compare not only, say Canadian gas companies with US gas companies to make sure we get that right comparison, but there’s also the size of these companies. If you could also talk about the scale of a US company average versus Canadian companies.

Eric Nuttall:

Yeah, sure. So last time I joined you, we would’ve been just beginning to talk about the twilight of US shale. So the belief that we had then that I would say has been completely validated, and that is US shale companies through the worst pricing environment drill their very best acreage, and they went from, what we call a tier one rock to tier two, tier three. So drilling less and less productive rock. Back in 2023, I don’t think any companies were really admitting to it. And it’s amazing just in two years time that conversation has gone from, there is no problem to, well, maybe there is a problem, but it’s not us, to now it is, well, we’ve got five years of high quality inventory. Those other guys only have two or three.

And so it’s been a rapid change in that conversation and that’s really important from both what I call the micro and the macro. On the macro, the world has been so reliant for US shale production growth over the past 10 years. It’s been by far the biggest source of incremental barrels. I think that’s coming to an end, depending on price, we think US oil production or shale production at least is in a permanent plateau to decline.

From an investment perspective, as you said, the US companies I think really stole a lot of the oxygen from the room for those few people that actually want to own energy companies. They were attracted by the larger market caps, the better liquidity, the stocks just tended to do better for a while. And I think as investors are awaking to that these companies, like to a company all have inventory challenges. It’s just a matter of degree. And as that lends itself to a more positive outlook for the oil price, I think energy investors are going to search the world to say, okay, there’s this bullish setup for oil, OPEC production, we’ll talk about capacity, that’s going to be zero by midpoint next year.

The world’s losing or has lost the largest source of supply, where can we get size and scale in an investable jurisdiction? You’ve got four in the world, you’ve got Venezuela, Iran, Saudi and Canada in terms of size and scale. Then when you apply the investability filter to it, it really ranks Canada very well.

Peter Tertzakian:

So just to get back to that barrels to barrels comparison, what you’re saying is that the US shale, which is very short-dated because of the very rapid production declines after you drill a well versus for example, the long-dated oil sands, which is much more akin to a mining operation, where the declines are very shallow, so you can produce it for a long time without a lot of maintenance capital, versus again, going back to the shales, which you have to keep drilling like a treadmill, to keep the production flat, let alone grow.

Eric Nuttall:

And to add onto that also where the quality of your inventory doesn’t decline over time. What we’re seeing in the US, both for natural gas and for oil in the Permian and the Marcellus, you’ve got erosions of anywhere from two to 3% if you evaluate a well on a per-foot basis.

Peter Tertzakian:

Can you compare then… Now getting back to the valuation multiples, and as Jackie said earlier, oil and gas companies in Canada have risen by 15% relative to American ones. You’re saying that there’s a realization of the quality of the Canadian company that wasn’t there before?

Eric Nuttall:

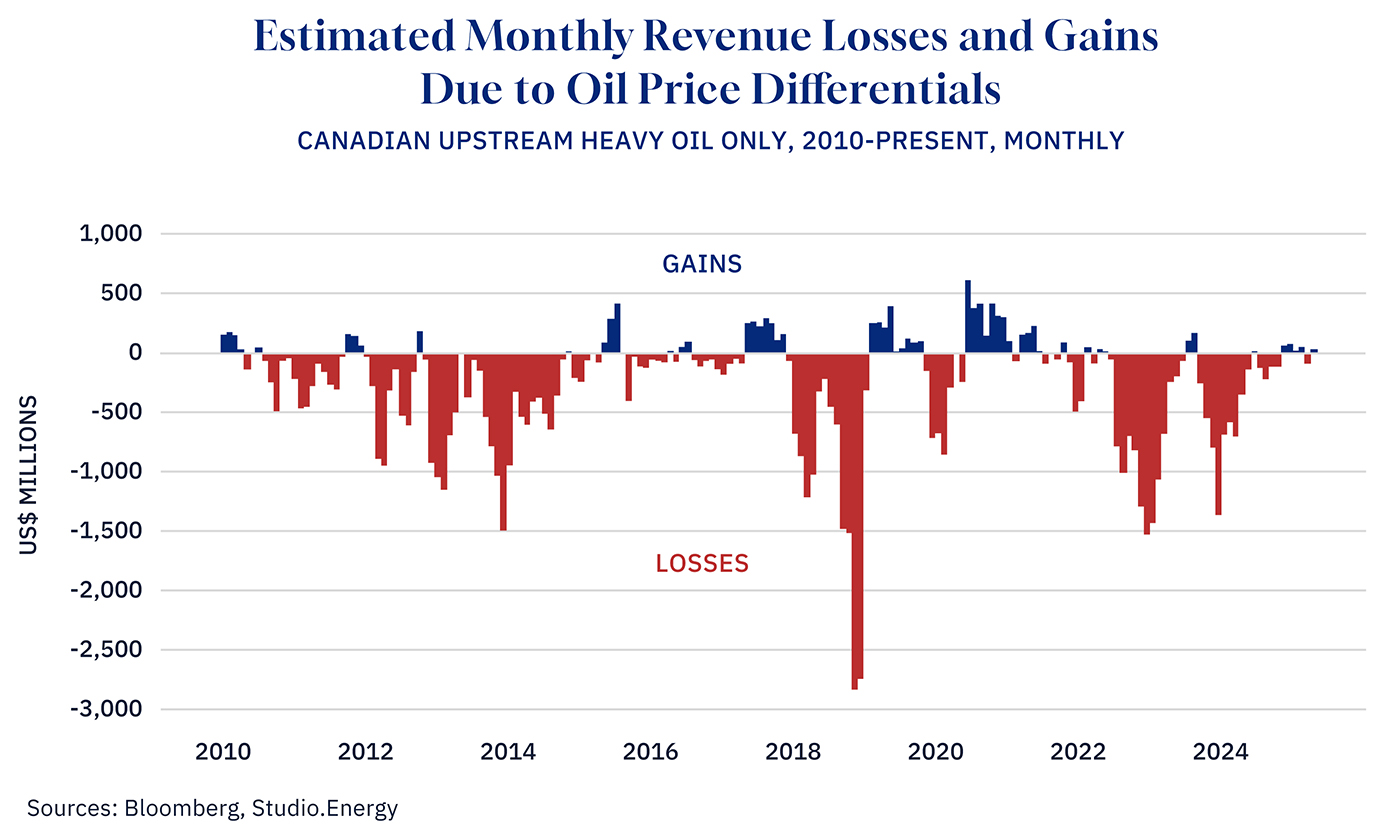

I believe so, and especially something that’s near and dear to our heart, which is share buybacks, the ability of companies to retire shares funded out of free cash flow to drive a re-rating because those remaining shares day after day, week after week, month after month become more and more valuable, when you’re facing a massive decline rate. It’s in the mid-forties, depending on who you ask, 42 to 45% base decline rate in the United States right now for shale, because you’re sprinting on that treadmill so quickly, the availability of free cash flow is not nearly as much as it is for a Canadian oil company where depending on how you define declines, you’re facing, let’s say 10 to 15%.

So it’s that additional free cash flow that I think is making Canadian oil companies way more attractive than the US at the moment.

Jackie Forrest:

And the other thing maybe that isn’t fully baked in yet is the fact that there’s a lot of reserves on the Canadian companies compared to the Americans.

Eric Nuttall:

Absolutely.

Jackie Forrest:

Yeah. And our shale gas, we have the, what do you call it? The treadmill. We have the high decline rates on our shale gas, but we have a lot more resource potentially than some of these US companies as well. All right, we’re going to get back to how shareholders are thinking about share buybacks here, because that’s a question that we have for you. But let’s talk really quickly about your view on oil price. Over the weekend we learned that OPEC wants to add even more supply to the market and the price of oil’s quite resilient, near $63 I think at the time of recording, per WTI.

And actually, a lot of people say it’s kind of too resilient, if you look at what the IEA is expecting over the next few quarters, it’s like three to four million barrel a day oversupply. Now we have the news of even more oil. So why are prices staying resilient and what’s your view on this change in OPEC’s direction?

Eric Nuttall:

So I think we would need the entire podcast to throw enough stones at the IEA. So let’s set their number aside. Those more credible numbers, like in energy aspects for example, they are still expecting 2 million barrels per day built, and if that were to actually come to pass, the inventory glut would be more than double what it was during the peak of COVID. So that’s not, to call it a forecast. That’s what the arithmetic may add up to, that’s not a reasonable outcome because OPEC will act. There is the massive amount of uncertainty right now in terms of, we’ve had the unwind of the original voluntary deal by OPEC members. As you point out over this weekend, we’ve had a further unwinding of 1.66, and the mistake people are making is they’re adding those numbers up and saying, “Oh my God, we’ve got 6 million barrels per day, whatever coming to the market.”

Much of that production was air barrels. It wasn’t actual volumes that were hitting the market. Secondly, there’s been massive cheating on the part of almost all countries to those deals since they became into existence. Now, Kazakhstan and Iraq, two notable examples. For the oil bulls, they’ll say, “Well, look, we’ve had this massive unwinding of the deals and the market’s fully absorbed it and inventories haven’t gone up,” because they’re looking at, what’s called visible stocks in OECD countries, mainly the United States.

China has been a massive buyer of barrels this year. They’ve been adding to their SPR, the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. They’ve added about 80 million barrels so far. And so my contention is, were it not for that SPR buying, you would’ve had builds in the more visible areas which are more impactful on price. So for now, the things that I’m watching, literally when I wake up in the morning, I’m pulling up things like Saudi Arabian oil exports, Kazakhstan oil production, Brazil and Guyana exports because I do agree in the very short term there’s a lot of oil coming to the market.

We have Guyana, and FPSO is ramping up now. It’s 130,000 barrels per day as of this morning of new production. There’s a couple FPSOs coming online in Brazil that’s going to add 400,000 barrels per day of capacity. There is actual production coming from OPEC members, mainly Saudi, and especially during the summertime, they burn a lot of oil for air conditioning that’s now coming to an end. So we’re tracking exports, which now point to almost 7 million barrels per day for September. That number’s early. So net-net, there’s a lot of uncertainty to have high confidence in the price over the short term. What makes me really constructive at some point in, I think early to mid-2026, is the world is waking up and realizing there’s a lot less OPEC spare capacity than what most people thought. And it really resides with Saudi. And so as His Royal Highness Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, the Minister of Energy of Saudi Arabia is really in the driver’s seat.

And so when we think of the world where, I think our views on long-term oil demand are in sync, this notion of peak demand is just absolute fantasy. I think the demand for hydrocarbons is going to grow longer and stronger. We’ve lost US shale production, which has been the biggest source of incremental barrels over the past decade, that has come to an end.

And once we get past 2025, a lot of the big projects from the Guyanas and the Brazils and even Canada are coming to an end short-term. And so there’s a line of thinking that thinks that non-OPEC supply, which is about two-thirds of total oil supply, is actually reaching a peak to plateau this year to early next year.

And then you would’ve said, “Well, that’s fine because there’s all this spare capacity held by OPEC,” but now what we’re learning is much of that was fictitious as well. And so the holy grail is demand growth far more than consensus, so long the consensus believes, you’ve lost historical supply and now spare capacity within OPEC has not just been normalized, but it’s actually been neutralized.

Peter Tertzakian:

Let’s talk about the spare capacity in terms of percentages. So whether the numbers, correct me if I’m wrong, there’s going to be spare capacity about 3 million barrels a day on pushing 105 million barrels a day of demand?

Eric Nuttall:

My own number on spare capacity now is 2.1 million.

Peter Tertzakian:

2.1. Okay.

Eric Nuttall:

And we’re consuming roughly 105.5 million today.

Peter Tertzakian:

So I mean this is just mental math, 1.8, 1.9%, which is very thin, and that 2.1 million barrels is figuratively or literally the bottom of the barrel. These are the lower quality crudes. So there’s not a lot of slack in the system for future growth.

Eric Nuttall:

And it’s an interesting pivot because Saudis always maintain spare capacity in the event of the geopolitical disruption. And I think it’s an interesting topic to get into. Okay, why are they pivoting? I’ve been in Riyadh a couple times a year for the past couple of years, and I think through public speeches that you can track, Saudi leadership has expressed this lack of appreciation that many people have had for Saudis investment in that spare capacity because it’s an enormous investment to maintain productive capacity that you’re not putting onto the market, therefore you’re not getting any revenue.

And so I think this is a very important shift on Saudis’ part, where in public speeches they’ve said, “Look, at anytime we have spare capacity, the US president is calling us up saying, Hey, why don’t you add those barrels because we want the gasoline price to drop heading into an election.” And so without that spare capacity, we are way more exposed to an actual supply outage from geopolitics, which we haven’t had yet but-

Peter Tertzakian:

So would you say the Saudi strategy is to gain market share now, position itself for higher prices sometime in the future, potentially not more than a year or two out?

Eric Nuttall:

No, I don’t. I do not think that Saudi’s battling for market share. I think what they’re trying to do is kind of cleanse the book, so to speak, where a lot of OPEC members have said, “We can produce X.” Meanwhile, they’ve produced at 70% of X and they’re all going through an exercise next year of resetting baselines. So I think by effectively going, not to say max capacity, but by resetting these ceilings that countries are exposed to, it’s really going to reveal, okay, what is the actual productive capacity, sustainable productive capacity of a lot of these countries?

And I think what it’s going to bear witness to is, there’s a lot less capacity in the system. There was a lot of chronic cheating that was occurring for the past year and a half, and the oil market is a whole lot tighter than what we would’ve thought six months ago.

Peter Tertzakian:

Just as a side note, a typical manufacturing system of widgets or products has spare manufacturing capacity of about 10 to 15%, so a spare capacity of less than 2% on this global system called oil is really thin.

Jackie Forrest:

Well, if Saudi has decided we’re not going to just keep 1 million barrels a day always on the sideline, that’s really dampened the reaction to potential outages. There’s going to be much more volatility in the oil markets without that spare capacity, especially on the upside.

Eric Nuttall:

And like we need more volatility.

Jackie Forrest:

Yeah. Talking about no volatility, how about natural gas in Canada? It’s been very low for a long time. Last three months, I think ACO has averaged about 75 cents and for the year to date, it’s only about 1.50 bucks. Of course, we have the very important startup of LNG Canada, but it takes a while to ramp these projects up. What are your expectations for North American Natural Gas and then specifically Canadian gas? Because it’s just been difficult.

Eric Nuttall:

Yeah. So we’ve been negative to neutral oil for the past three, four months for all the reasons that we spoke about, this fear of a wall of oil coming to the market Q4, and [inaudible 00:19:43] and such. And so we thought safe harbor might just be natural gas stocks because at the time there was the belief that we’ve got these LNG facilities coming on, both in Canada and the United States, there’s new sources of demand from AI and data centers, and then sure enough, mother nature provides one of the coolest summers, I think in 10 years. And so that’s taken some of the froth or hot air out of the price short term. I think natural gas has gone from being a bridge fuel to becoming the fuel to satisfy incremental meaningful demand for power. You’ve done great podcasts. You’ve highlighted how power demand in the United States was flat as a pancake for many, many years, and beginning in 2024, it’s really starting to inflect now.

I hang my hat on LNG, you’re going to grow from roughly, US is exporting about 15 and a half BCF a day now, that’s going to grow to about 29 to 30 of feedstock by the end of this decade. You’ve got AI data centers, you’ve done some great podcasts. I think the bookends are rather wide. We just look at companies like GE Vernova, highlighting about eight BCF a day of backlogs for their turbines, and there’s other sources. And so I find natural gas from the demand side, at least for LNG and power, it’s a lot easier to sink your teeth in.

When it comes to weather, of course, we just hope for a normal winter coming, we think that a lot of the excess storage can be easily worked off. And then when we speak to producers in the United States at least, $4 in MCF seems to be their line in the sand where they’re not willing to meaningfully grow production, and even growing, I’m talking about low single digits.

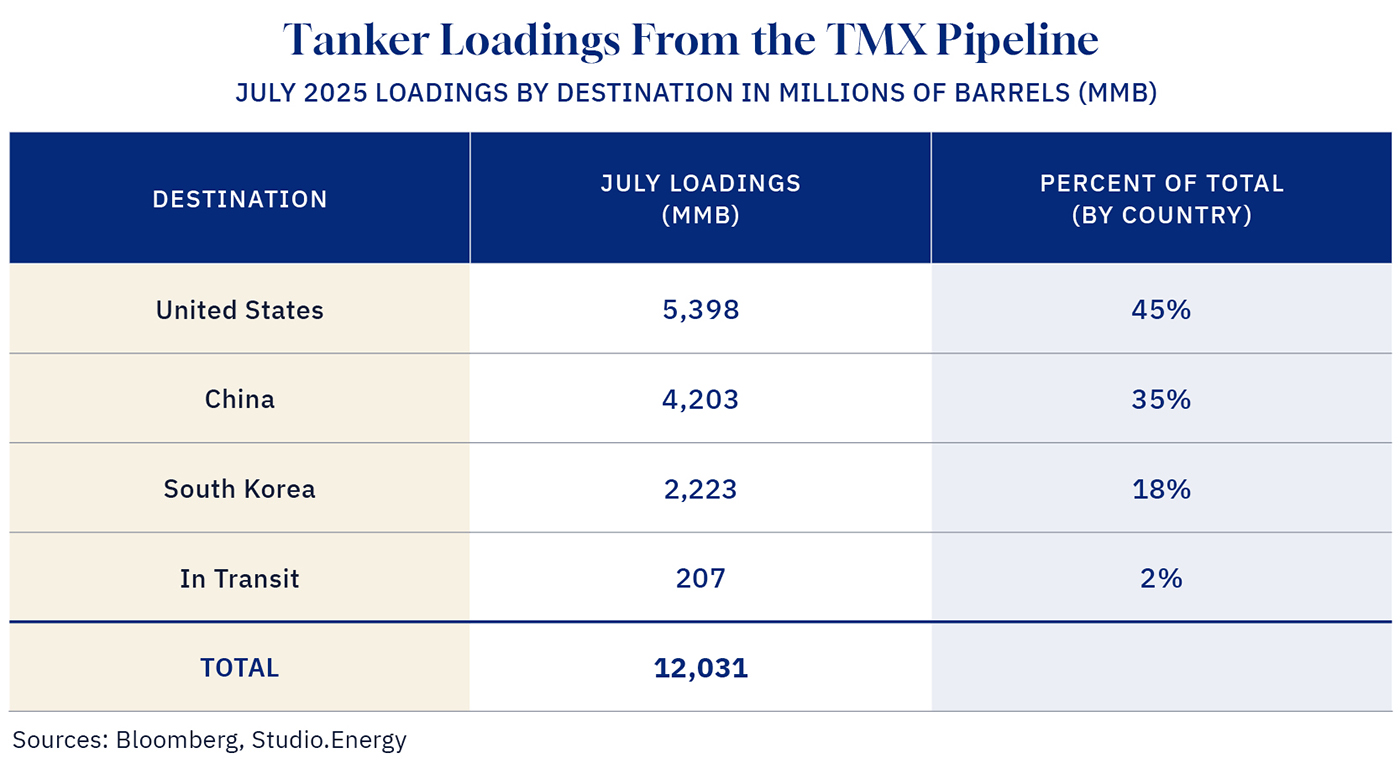

So when a TC Energy comes out and says, “Well, gas demand is going to grow by 45 BCF a day by 2035,” and we’re producing, let’s say 125 in North America, give or take, that’s a pretty bullish setup. For Canada, our challenge has been, LNG Canada was supposed to be a massive catalyst just as TMX expansion was for heavy oil. What was different was we had a few natural gas producers front run that demand shock, if I can use that term. And so a lot of these short term benefits were negated.

We hope that Canadian gas producers take a page from their US peers who have been way more responsive to curtailing production, dropping rates, et cetera, when prices fall. LNG Canada should lead to about $1.10 differential, should, I hate the word discipline, but if producers just acted a little more intelligently to sub $1 gas prices.

Peter Tertzakian:

But let’s explore that a little bit, Eric, because natural gas, yeah, we’re basically giving it away at 75 cents. Meanwhile, in the US, it’s anywhere between 3 and $4 US. But effectively it’s a byproduct. Natural gas is a byproduct and the value is in the stream of liquids that come up with the natural gas in the same well. And so how do you think about that as… Your comment just now would suggest that natural gas producers are drilling for natural gas, but in fact they are drilling for the liquids which are much higher value and getting surplus natural gas as a byproduct? Isn’t that the way to think about it?

Eric Nuttall:

That is a very fair comment to make, however, there are some producers where they’ve got a fairly lean liquids component of their overall stream, without getting specific, and they’re growing their gas volumes next year by 7% into an already, I’d say, let’s call it oversupplied or adequately supplied market.

To me, that just doesn’t make sense. I’d rather take the CapEx being spent on those wells either diverted into liquids or even better, take advantage of depressed share prices and go buy your stock instead with it.

Jackie Forrest:

Okay, well, let’s get into the equity markets because that is what a lot of companies have been doing, not growing and giving more money to their shareholders. Let’s talk about M&A first. You talked about the compelling case for Canada because of our reserves and in the case of the oil sands, our low decline rates, and we have seen more M&A in Canada in 2025. We talked about it on our previous podcast, but there’s been a number of deals. The big one is Whitecap with Veren, Vermillion acquired Westbrick, Tourmaline also acquired a company. From your perspective, do you generally like to see these companies getting larger and why?

Eric Nuttall:

Depends if I’m on the receiving end or not. It’s a little sensitive right now with MEG, I feel like I’m losing a best friend right now. Let’s talk about M&A in the context of… Going forward, I do think, as we talked about, US shale companies are going to have to replace depleted inventory. Canada is the only place where they can apply their skillset. We’ve got a friendly jurisdiction, we’ve got depth of administratory, et cetera. So I do think you’re going to see US companies coming to Canada soon, and in fact, during Stampede, the talk of the town was that you had a very large natural gas producer coming in, kicking the tires, so to speak, in a couple of panels, et cetera.

What we’ve seen more recently, I think, you mentioned Whitecap and Veren, you’ve got Strathcona/Cenovus and MEG, I think what you’re seeing are companies taking advantage of lulls in sentiment and being opportunistic.

We were a very significant shareholder in Veren. We had added to the position late last year as the stock weakened off on some poorer well result from a different completion technique. And the sentiment is so horrific. The market just said, “Well, look, there’s a quality [inaudible 00:25:12], et cetera.” The stock fell. We saw a huge opportunity. And I think whitecap buying them, it was them also recognizing that opportunity and realizing that we were months away or weeks away from an inflection and sentiment.

With Strathcona and MEG, what I think Adam Waterous, and Adam is, how can you not respect Adam Waterous? He’s created a fortune for his investors. I am at the same time a little miffed with him because what I think he was doing was taking advantage of weak sentiment on oil and putting into play what was a very unique story.

MEG has 35 plus years of state flat inventory, in my opinion, a very shareholder-friendly management team and board that were on an ongoing basis hoovering up stock. Low to no growth, huge free cashflow, and using that to buy back their shares. We thought that they’d be able to buy back about half of their company over the next five years just through buybacks. And so I think Adam was counting on Cenovus having a low cost of capital. They’ve been plagued by downstream, they were, especially then, a month ago or whatever, trading at a pretty big discount to their peers.

I think his thought process was we can capitalize on very poor sentiment and go after one of the last remaining crown jewels and the only other likely bidder has a low share price, they won’t be able to compete. So I think what we’ve seen in Canada so far is more opportunistic.

What I think we will see down the road is, out of a necessity, US companies having to replace their inventory and coming to the Montney and Duvernay. I think the oil sense is probably a bridge too far, but I think you’ll see Montney and you’ll see Duvernay transactions.

Peter Tertzakian:

I want to key in on this word opportunistic. Take that a little further here, because I’m not sure I completely agree that it’s just opportunistic based on, say, low valuations. I mean, we do know that scale matters in the business, in any type of business, the scale matters because it helps to reduce your costs with buying power for services and so on. But if we think about the oil and gas producers, historically there’s been a fairly wide gap between what the buyers are willing to pay versus what the sellers were willing to sell at.

In other words, there was that bid ask spread as they say in the business. I get the sense that that’s narrowed, that the sellers are now willing to sell at a lower price versus what the buyers were willing to pay. I mean, can you comment on that? I mean, the times have changed. There’s almost like a capitulation that scale matters and that small sellers need to sell to the bigger ones and they’re willing to actually take a lower price.

Eric Nuttall:

I’m not going to totally disagree, Peter. I do think that each transaction is unique, and having spoken to the Duvernay team, the morning of them announcing a massive premium, there was not joy in their voices, speaking with MEG individuals, I don’t think this is capitulation. This is them having to react to being put into play. I do agree, size and scale from an equity perspective matters. There is a battle for relevancy. There is zero appetite. We run still what is the largest energy fund in Canada. We don’t buy small caps. We can’t. There’s no liquidity. Even mid-caps, we own mid-caps, but it is more difficult to… You want to move around 20 or 30 million shares. It has its challenges, and so that larger market cap eliminates one objection that investors or potential investors may have.

So I do get that. I do see the cost synergies, but at the same time, when we’re on the receiving end, my fear is that as sentiment remains poor, and I see it every day, my inflows/outflows are the best proxy for sentiment in this space.

And we lose through redemptions of all public information every single day for the past year and a half, and we have, what I consider one competitor and he’s a great guy. Same thing for him. And so the sector is bleeding money every single day, and so sentiment is poor, and my worry is we’re going to lose some of our crown jewels at modest premiums where if there was a bit more patience, the money’s going to be made in the wait. You look out two to three years at a much, much more bullish outlook for oil and natural gas.

We see very meaningful upsides, and so I worry that investors are going to tender to a 10% premium or 20% premium when we think you can make multiples of that over time.

Jackie Forrest:

Okay. Well, you’ve mentioned share buybacks as very important. When a company buys back their shares, doesn’t it sort of say that they don’t really have any attractive opportunities to invest in? And I think up until now, Canada didn’t have enough pipelines for oil or gas, and that was kind of true because if everyone grew and we saw that in 2018, we’ve got a problem, right? But now with the advent of TMX, maybe expanding TMX, maybe a Prince Rupert pipeline, maybe more beyond LNG Canada phase one, there’s the potential for more projects because Mark Carney’s nation building projects is giving us hope that we will get some new infrastructure.

How do you look at share buybacks in that context where companies actually could grow? Would you rather them grow to get a return for you if they could?

Eric Nuttall:

My fiduciary duty to my clients is to make them money through investing in the oil and gas energy equities. And so what is my highest confidence path to achieving that? What you said is, I think for other sectors, why are you buying back stock? You’ve got nothing else to invest in. I think that is very reasonable. However, when you look at things through the filter of today, where the sector bleeds money every day through outflows, people are net sellers of energy stocks. They have been for the past year and a half, there is still ignorant views of peak demand, abundance of supply in US shale, all these different things.

I am not confident that a share price of an oil company will go up or natural gas company will go up if you just grow volumes. What I am absolutely confident in is if you buy back half of your stock, those remaining shares are becoming much, much more valuable because the ongoing share buybacks and even dividend potential grows exponentially.

And so that’s the philosophy that we’ve had for several years. We can easily point out that there’s a very high correlation between share price appreciation and those companies that have been aggressively buying back their stock. And so we just think it’s a surer path to getting share prices to go up in an environment where the sector is bleeding money every single day.

There will come a time, however, where that changes. I do think we’re heading towards, not to sound dramatic, but the world’s facing a supply crisis in the coming years, and there will be a massive call on incremental barrels, and there are only so many countries that have the ability to satisfy that. Canada is going to be one of them. But I think the atmosphere and the sentiment will be vastly improved then versus where it sits today because it’s a very similar conversation versus two years ago. It’s just people just don’t care about this space. It’s become very complicated. It’s become very volatile, very complex. And from a retail perspective, which is a massive source of buying, they’re much more happy buying Nvidia and Bitcoin, where seemingly they make all-time highs every day than versus the brain trauma required to invest in energy stocks right now.

Peter Tertzakian:

Well, given that you say the people are selling shares, it’s bleeding from the perspective of people finding other investment opportunities. Meantime, the industry will still generate $170 billion of revenue, and royalties and taxes to government will be over $30 billion, which is no small amount of change given the deficits that we see in government. And if you buy into the notion that we aren’t going to be in a supply crunch globally, and it is Canada’s opportunity, it would argue that now is actually the time to build more export capacity, to position ourselves to seize this moment coming up. What are your expectations that we will be able to do that under the new Carney liberal government that have signaled major infrastructure project building, including oil and gas export facilities? Are you optimistic that that’s going to happen?

Eric Nuttall:

You’ve had some fantastic guests on to address that topic. And I think the common view is, we’ve had a lot of talk. There’s been a lot of positivity. The right things are being said. I’ve yet to see any real action, and I believe Parliament is going to be resuming soon. I’m not confident just yet. We surely have a more sophisticated government in place now than we’ve had over the past decade. I do think there is a market demand for our product, both for LNG and for oil. I’m not yet confident that you’re going to have the private sector stepping up to satisfy that demand for a variety of reasons.

So I think it’s still too early to tell. I’d like to see some concrete action as opposed to just a lot of press conferences and talk.

Jackie Forrest:

Now, Eric, if we actually want to have these export projects, we actually need supply to fill them. And so producers are going to have to grow, and you’re telling them they can’t grow. So I’m feeling less optimistic talking to you that we’re going to have producers sign up for these.

Eric Nuttall:

It is a bit of a conundrum, and I admit to perhaps I’m part of the problem. Again, it goes back to, you’ve got two paths to have a rising share price because in the end, that’s what I think boards need to be worried about. And so path one is, let’s grow production. Let’s hope sentiment improves. Let’s hope people care. Path two is, let’s just buy back 15% of our stock a year. And there’s a surety that the remaining shares become more and more valuable with each passing day, and week and month, and especially as we’ve beaten this horse to death. But in a sector where there’s an abundance, massive wall of free cash flow, and yet the sector experiences investor outflows on a daily basis.

Peter Tertzakian:

So you’re favorable to share buybacks obviously now, but say you had a lot more certainty that export pipe would be built for both oil and gas, and able to attract high value markets. Would you then as an investor be more favorable to the companies that you own to plow money back into the ground instead of spending it on buying back shares to grow production and fill those pipes?

Eric Nuttall:

I think if the outlook improves from a perspective of OPEC having meaningful spare capacity for many years, and so at a time when there’s a lot of OPEC spare capacity, so in other words, they’re withholding barrels from the market. Why are we, Canada and the United States, when we’re a higher cost source of barrels, why are we adding barrels onto the market? The world’s going to be changing very soon where OPEC, and I do think this is a big shift. We’ve gone from OPEC not just normalizing spare capacity, but now indicating that they’re actually going to be eliminating spare capacity effectively over the next, I’m going to say nine months to a year.

So that’s a very, very different world than we’ve been living in. And so when there’s an actual significant call on those barrels, I think that’ll translate into improved investor sentiment, and then that will potentially green light companies from growing production more meaningfully than they have in the past couple of years.

Peter Tertzakian:

But that green light is somewhat dependent upon investors like you because when CEOs come to Bay Street, then they go to Wall Street and they speak to the portfolio managers, and you are effectively as a shareholder, guiding them as to what to do. So they look to investors to say, “Yes, it’s time for us to put money back into the ground versus buying back our shares.” I think this is a fundamental thing that we need to wrestle with. We don’t have to answer it right now, because everybody’s talking about building pipe, but not a lot of people are talking about how to fill the pipe.

Eric Nuttall:

It’s a very fair, and I appreciate how there’s tensions between different viewpoints as well. I’m sure government officials have a very different list of priorities than what an investor may, and it’s not easy, but neither has it been an energy investor for the past five years. Energy investors, the owners of these companies, I admit, government owns the resource but we own the companies. Both on an absolute and relative basis, they deserve to be rewarded for the patience over the past several years, because it’s been very difficult to be an energy investor.

Jackie Forrest:

Well, and we have a lot of national goals. And one thing, this has been a great conversation, Eric, we’re going to wrap it up here, unfortunately, we have so much more we can talk about. But one thing that’s on my mind, you talked about a green discount in 2023 because of the liberal policies. Most of those liberal policies are still here today. We’ve got the cap on the oil and gas emissions. It’s not in law, but it’s certainly still being talked about. We’ve got rising carbon price that’s in law. We’ve got very difficult 2030 greenhouse gas emission reduction targets, if we really are going to build these pipelines and do more LNG, it seems impossible to meet these goals.

We’ve got a government that’s saying the right things, as you said. So how is the green discount for Canadian oil companies now? Do you think it’s been erased a bit with the change in share price relative to 2023 compared to the Americans?

Eric Nuttall:

I still think that if we got out of our own way, it would lead to another re-rate for our shares. It’s just such a lost opportunity. Like here we have one of the most attractive and profitable at size and scale oil and natural gas plays on the planet, and yet we continue to shoot ourselves both in the foot and in the head from these stupid policies.

And so I just hope that, again, a lot of the talk translates into action. No other country in the world would do to themselves what Canada is doing to themselves. And so I think we just have to wake up and realize that we’re losing our competitiveness. Look at LNG, the United States, they’re exporting 15 and a half BCFs. We’re at one roughly as of today. Think of the lost opportunity in that.

And so I’m hopeful, I’m kind of optimistic that we’ve got a government that is starting to see that and less guided by environmental dogma and more about getting paychecks and improving our fiscal state because we sure as heck have the opportunity to do it.

Peter Tertzakian:

Well, thanks for sharing that and all your other views, Eric. It’s been a great conversation all the way from talking about the supply side, OPEC, spare capacity, global oil demand, US versus Canadian companies and plays, consolidation, share buybacks, and now carbon policy. So I think we covered the full gamut in a very short period of time. It’s always great to get your perspective as an investor because investment is critical to any business and industry.

So we hope to have you back as our first time fourth time guest in the near future. Thanks so much for taking time out of your valuable day. Eric Nuttall, Partner, Senior Portfolio Manager at Ninepoint Partners. Thanks again.

Eric Nuttall:

Thanks so much.

Jackie Forrest:

And thank you to our listeners. If you enjoyed this podcast, please rate us on the app that you listen to and tell someone else about us.

Announcer:

For more ideas and insights, visit ARCenergyinstitute.com.