Commentary – Back to Gas Guzzlers and Driving More

Source: www.Dreamstime.com © Snehitdesign

“That thing must chug a lot of gas,” I said to my friend who was proudly running his right hand down the side of his big new SUV.

“Not an issue now,” he said as he stopped and patted the fuel cap, a confident gesture referring to low fuel prices. “Besides, it gets better mileage than the last beast I had.”

Those words will resonate all the way to Hampstead Cemetery in London, I thought. No doubt William Stanley Jevons, 19th century economist, would be smiling in his grave. His theories are being validated – yet again. “It is wholly a confusion of ideas,” Jevons wrote in 1865, “to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to a diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.”

Today’s data says it all.

Average fuel economy of sales-weighted new vehicles is up by 21% from the time when oil prices topped $147/B in 2008. Adding to already cheaper driving costs, US retail gasoline prices are down by 30% since the oil markets collapsed. Yet as Jevons predicted, consumers are eating up their newfound energy windfall by upsizing their vehicles and driving more. In the parlance of energy economics, this is called the “rebound effect.”

And consumption of fuel-burning equipment and fuel is certainly rebounding. After nearly five years of moderation, monthly sales of heavier vehicles with larger displacement engines, like SUVs and pickup trucks, are on the rise again relative to lighter vehicles. This past April over 55% of all vehicles sold in North America were pickup trucks and SUVs – up from a 50% average between 2009 and 2014. Although the efficiency of heavier vehicles has also improved, upsizing from a lighter car to a heavier truck equals heavier overall fuel use.

A 2007 study by the U.K. Energy Research Centre on the rebound effect found that when people have the choice to buy a more fuel-efficient vehicle their inclination is to rebound by up to 30% off the assumed gains. In other words, consumers trade in some of their potential gains by shifting to bigger gas-guzzlers and by driving more. This works against a 21% gain in average fuel economy.

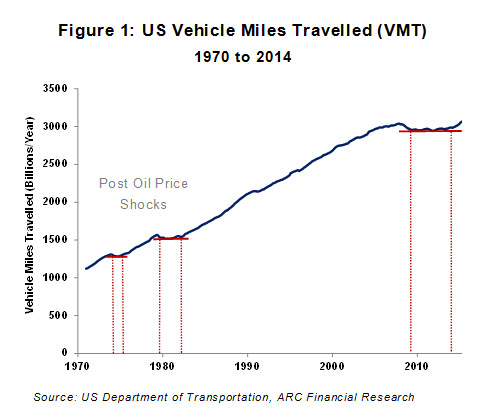

In fact, after flat lining for more than five years, Americans are starting to drive more. The vehicle miles travelled (VMT) indicator in the US is tracking a return to record levels this year, challenging the high set in 2007. By extension, US gasoline consumption set an all time high last week, with year-over-year growth already up by 3.4%. New consumption records are likely to be shattered this summer and the U.S. Energy Information Agency now expects that US oil demand will grow more than China’s this year.

But greater consumption on the back of cheap fuel and greater efficiency is not only an American phenomenon. Global oil consumption growth estimates for 2015 and 2016 are now expected to top 1.2 million barrels per day each year. More upward revisions are likely as long as oil and fuel prices stay as low as they are now. And if economies get healthier, the pull on the oil producers will be even harder.

This double cocktail of cheap fuel and better fuel economy is yet again a stimulus for gratuitous consumption that will contribute to another round of rising oil prices. Like watching a short YouTube video that keeps looping over and over again, the repetitiveness of this economic phenomenon we’re witnessing is nothing new. We saw it happen post both the 1973 and 1979 oil price shocks.

Although Jevons wrote of coal consumption and steam engine efficiency in his 1865 book The Coal Question, his dialog is fungible for oil and the machines that consume petroleum products: “It is the very economy of its use which leads to its extensive consumption. It has been so in the past, and it will be so in the future. Nor is it difficult to see how this paradox arises.”

No, it wasn’t difficult to see Jevons’ paradox as I opened the heavy door of the new SUV. “Nice machine,” I said to my friend. “We’ve come a long way since the steam engine.”

Then I thought to myself, but we haven’t traveled far at all in terms of behavior.