Decision Time

For the first time in four years there may be over $C 20 billion in the Canadian oil and gas industry that’s seeking direction.

Over the next few weeks, corporate leaders—influenced by their investors—will huddle over boardroom tables and make the most consequential decisions to our economy since the oil price crash of 2014.

In Canada, the price of a barrel of light oil is now close to $C 85. That’s approaching the range of where it was in the good ‘ol days, before prices were cut in half, sapping cash, investment and employment out of the economy.

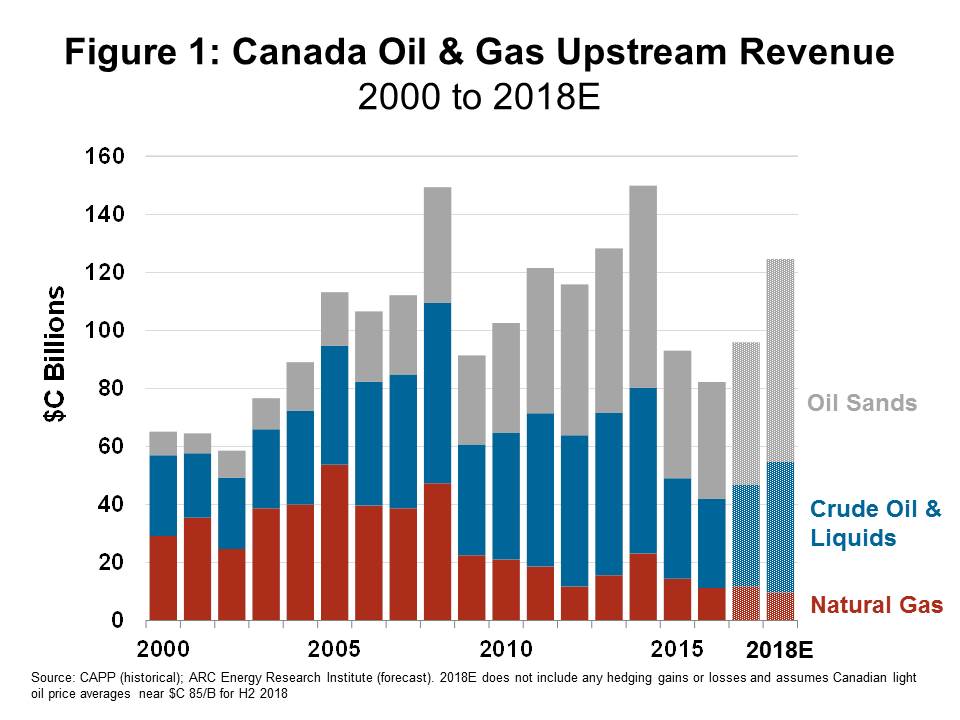

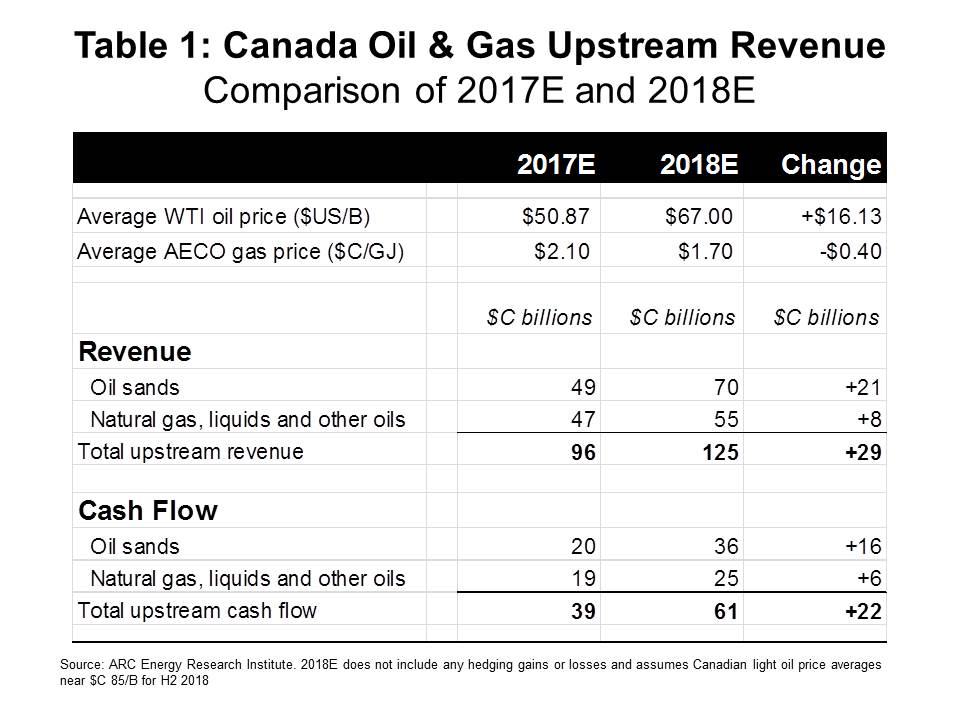

The recent nine-month run up in oil prices—from $US 50 for a barrel of West Texas Intermediate (WTI) to the high $60s—has given extra punch to Canada. On top of the near 20-dollar price rise, our sagging 75-cent Loonie amps up revenue and cash flow by over 30%. Much depends on if US oil prices sustain around $US 68/B, but if they do the year-over-year boost to 2018 revenue would reach $C 29 billion (see Figure 1). Total cash flow is expected to rise over $C 20 billion (see Table 1).

But where will the money go?

Hesitation abounds at decision-making tables. Nobody is talking boom amidst all the uncertainties. The situation is also curious because the traditional gearing between oil prices and other economic indicators are not meshing like they have in the past, at least not yet.

Most investors are neutral to the uptick in oil prices. Some stocks—notably oil sands and a few market darlings—have motored higher, but the broad response is still stuck in second gear. Toronto Stock Exchange oil and gas indices are up 14% over the last quarter, but year-on-year they’re stagnant.

Equity issuances are almost non-existent. A few years ago, investors had bought $C 6 billion of new stock from corporate treasuries by this time of year. The number so far is close to zero.

Never mind the investors. Companies now have cash flow, especially those that sharpened pencils and reduced costs during the downturn. The fittest survivors of the crash of ’14 are in the best position to take advantage of this price rally. Here are their options:

1. Pay down debt – An obvious thing to do for companies that have had the bankers noose around their necks for four years.

2. Give money back to shareholders –The first call on extra cash has been to give patient (and cranky) shareholders their money back. Many Canadian and US oil producers have been buying back their shares. Some have been increasing dividends. But this give-me-my-money-back mindset is coming at the expense of putting cash back into the ground.

3. Recycle cash into new production – The appetite to invest in oil sands projects remains low until there is light at the end of the pipeline. What oil sands companies do is of greatest consequence – their cash flow bump relative to last year is likely to be $C 16 billion.

Producers with a skew to dry natural gas won’t be reinvesting much; at under $C 2.00/GJ their product is coming out of the ground for free. Surplus production must clear. That’s why LNG projects are so important.

In the rest of Alberta, drilling budgets for hydrocarbon liquids should start trending upward; at these prices board members know that an extra $C 6 billion could recycle well into lighter oils. But there could be a cheaper alternative to drilling: buying somebody else’s production.

4. Buy other companies – Lackluster stock market activity has created plenty of “orphan” companies in the oil and gas eco-system. Potential bargains are out there for bigger fish with attractive valuations and cash in their gills. Historically, all it takes is a few good bites to start a feeding frenzy. And then the circling investors wake up too.

5. Invest the money abroad –For multinationals, Texas has been the calling for new drilling dollars. But any opportunity that’s too good to be true attracts the investor’s plague: cost inflation, brutal competition and price differentials. Fort McMurray caught that bug circa 2012. Today, Canada’s oil and gas industry has other issues, but contrary to belief it’s not easier to make money anywhere else. Every oil-endowed region has problems, so sending surplus dollars abroad is the least likely option for domestic companies.

As board meetings get underway, the decision-makers will have some tough choices to make. The environment for future oil and gas development remains fraught with vagaries, especially price stability. But all can agree that having some spare cash again is a good problem to have.