Commentary – Oil Storage Fixation Misses the Big Picture

Oil markets continue to debate the vagaries of how much crude and refined products are stored in big white tanks and floating carriers. The feeling is that there is too much sloshing around. That’s why the oil price is under siege again, down 10% in the past three weeks.

Meanwhile, the untold story is at the front end of the supply chain. The iron equipment that works to put oil into storage vessels is going idle the world over. Every week, an increasing number of drilling rigs are hosting weeds and barnacles. That’s of concern, because fixating on inventories for any product is a narrow thought process. Think of it this way: There are no worries when there is plenty of food in the fridge; but unease about the future sets in when farmers stop planting their crops.

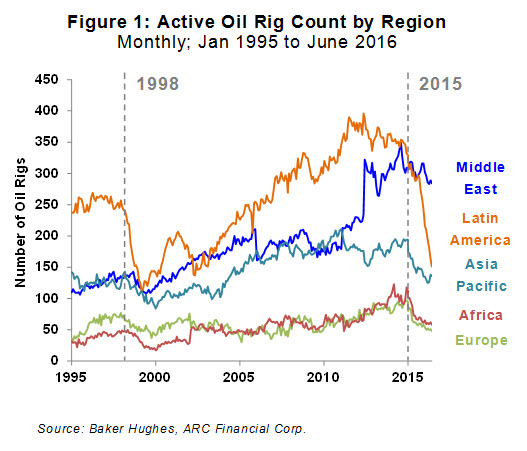

Our feature chart this week shows 20+ years of active drilling rig data (oil targeted) from Baker Hughes. Five regions outside North America are profiled: Latin America; the Middle East; Europe; Asia and Africa. Both offshore and onshore rigs are included.

Except for the Middle East, the number of active rigs in every region has retreated to mid-2000 levels. But oil consumption is going the other way; compared to 10 years ago the world burns over 10 million more barrels a day of the vital commodity.

Oil producers began slashing their exploration programs in January 2015, over 18 months ago. Back then there were 982 spinning drill bits outside Canada and the United States. Now there are only 677, a drop over 30%. And the number will go lower yet.

Latin America has seen the biggest retreat in the international grouping. Rig counts in Brazil, Colombia and Mexico are all down by over two-thirds, Argentina by 40%. High costs, bureaucracy and political issues are all exacerbating the impact of low prices. This is déjà vu: Our chart shows that Latin American producers also suffered hard during the 1998 downturn.

Oil drilling in the Asia-Pacific region is off by 22% since January 2015. There are a lot of countries in this group, but the meaningful rig counts are mostly in China and India. Although the downtrend is choppy, the count has popped up by about 10 rigs lately. But it’s hardly a recovery. Recent commodity price weakness will make the gravity pull harder.

African and European activity trends are very similar in size and character. Europe is mostly offshore North Sea. Africa has some onshore, but a lot of offshore too, especially off the west coast. Activity in both regions fell abruptly in the first half of 2015, then started to taper off a year ago. Further spending neglect is inevitable in both Europe and Africa.

Middle Eastern exploration activity has eased off the least, given the region’s low cost and ambition to fight a global price war. A big jump in rigs back in 2012 is attributable to Iraq’s return to the market. Rig counts in Saudi Arabia are still holding steady, as the Kingdom continues to tap into plentiful reserves. But the overall trend in this prolific region is still down as a dearth of capital squeezes exploration spending like everywhere else.

And what of North America? The market is fixated on the US oil rig count, which has crept up by over 50 rigs since the price of WTI oil popped its head above $45/B. But 50 is not much; considering that 75% of the 1,500 rigs working at the start of 2015 are still parked – an even greater decline than in Latin America. So, is it realistic to think that a handful of US drilling rigs going back to work can offset universally declining activity elsewhere in the world?

It’s unlikely. Admittedly, rig productivity is considerably better today than in 2015 – each working rig can deliver more oil to market. Prolific US oilfields like the Permian in Texas have been impressive in their ability to deliver large quantities of oil with new processes and technology. But over 85% of the world’s oil production is outside the United States and productivity hasn’t improved enough in 18 months to offset the rapid fall in upstream spending and activity.

Global producers are broadly divesting of exploration activity at the same time as consumers are investing in 90 million new hydrocarbon-consuming vehicles each year. Inventories may be full for now, but nothing in the global drilling data is comforting about future oil supply meeting still-growing consumption.