Commentary – On the Right Side of History, at Last

Photo: Peter Tertzakian

Photo: Peter Tertzakian

Western Canada is in a deep freeze. The US Midwest is buried under snow. An Arctic blast is expected to hit the Eastern and Central United States in the next week. The frigid weather is causing people to crank-up furnaces and heaters across the continent. Power consumption is surging too. In Alberta, power use hit a new all-time high for peak winter load last week.

The only ones reveling in these freezing temperatures are North America’s natural gas producers.

Last Friday, the intense weather-driven demand for natural gas combined with expectations of ongoing freezing conditions pushed benchmark US prices at Henry Hub to a level not seen in almost two years, $US 3.75/MMBtu. Prices have weakened slightly since Friday’s high, as newly updated weather outlooks are now predicting a greater chance of warmer temperatures before the Christmas holidays.

Over the past few years, weak natural gas prices have been the result of a prolonged supply glut. The initial cause was a “polar vortex” that gripped the continent in the winter of 2013/14. Back then, a lengthy cold snap set low temperature records on the East Coast, boosting natural gas consumption, and spiking prices to over $US 5.00/MMBtu in early 2014. In turn, the high prices resulted in more drilling, pipelines and a gush of new natural gas supply. Associated gas from robust oil drilling amplified the surplus. Even industry veterans were surprised when year-over-year American production grew by 7 Bcf/d or 10% over the course of 2014.

The hangover from the 2014 supply binge extended into 2015, when natural gas markets continued to be oversupplied. The situation only got worse when the exceptionally warm “El Niño” winter of 2015/16 sapped demand, causing prices to sink under $US 2.00/MMBtu.

This recent history illustrates how weather drives unpredictable price volatility in natural gas markets. The relationship between weather and price has grown stronger over the past 15 years, as the amount of weather related demand has increased by more than 8 Bcf/d over that time frame (see past blog “Weathering Volatility in Natural Gas Markets”).

Assuming that Old Man Winter continues to linger into January and February (a critical, yet still uncertain assumption), price could once again spike above $US 5.00/MMBtu as it did in 2014; especially when you consider the underlying supply fundamentals are weaker today, compared with back then.

As a result of low prices inflicted over the past few years, natural gas field activity has slowed to a snail’s pace. The number of US rigs targeting gas is only one-third the level of 2014. If prices strengthen this winter, it could take some time for supply to respond, being that it has to ramp up from this low level. A shortage of new takeaway pipeline capacity from the prolific Appalachia region this winter may be another constraint. Combine this with the fact that, as a result of dwindling US oil production, associated gas is meaningfully declining.

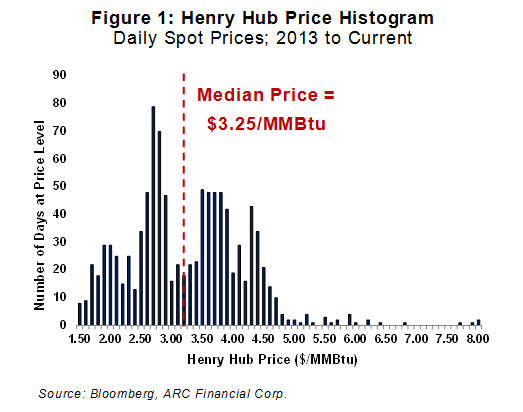

While the current price boost is welcome news for natural gas producers, history has shown that North America’s low cost, abundant shale gas resource has a way of mercilessly capping the price upside. Figure 1 shows a histogram of daily natural gas prices at Louisiana’s Henry Hub going back to 2013. While there are some outliers, prices have mostly yo-yoed between $US 1.50 and $US 5.00/MMBtu, with a median at $US 3.25/MMBtu. Only one-third of the data points are over Friday’s $US 3.75/MMBtu high mark.

There are two main forces that keep price oscillating equally on either side of this median. On the demand side, the weather swings back and forth on either side of normal. In other words, predicting gas demand is about as forgiving as predicting long-term weather. On the supply side, plentiful resource and new production techniques have created a system that can turn on and off supply within a season, depending on the commodity price, that is largely dictated by the weather.

Figure 1 illustrates why, if higher prices make an appearance this winter, that producers should enjoy them while they last. Post the shale gas era, history shows they do not persist for very long.