A Disorderly Energy Transition

Climate crisis plus energy crisis does not equal a good path to net-zero emissions. Policy wonks at the upcoming COP26 conference in Glasgow later this month will have a tough time with this calculus.

It’s been a while since the phrase energy crisis has been thrown around. When I hear it, I have déjà vu to the 1970s, the late-2000s and other lesser episodes in between. I reflect on societal hardship, ugly politics and uncertain outcomes.

Today, a panoply of numbers is pointing to a looming energy deficit that may rival big ones of the past. Volatile commodity markets agree: The price of oil, now over US$80 per barrel, has doubled in the past year. Natural gas in some markets has shot up five-fold. Coal, the fuel with more lives than a black cat, is setting record high prices.

The contagion of energy price inflation is happening from Germany to Brazil to China, and it’s on its way to a gas pump, furnace and wall plug near you.

We are witnessing the perils of a disorderly transition, the consequence of mismanaged efforts at decarbonizing the world’s energy systems.

Dismissing the importance of fossil fuel systems before having sufficient, secure and affordable clean energy substitutes is only half the problem. The other half is more ominous and reflective of past crises. Western countries have allowed the control of oil and gas markets to regress into the hands of countries that have a history of leveraging political muscle with their energy supply.

In business, the word ‘transition’ embodies the premise that people replace old products and processes with new. Sales of the latter grow and the former wane.

For example, paper map sales go down when GPS unit sales go up.

I didn’t stop buying maps, nor took them out of my glove box, until I was convinced GPS was leading me to the right destination and that there was ubiquitous signal coverage wherever I went.

Maps may be a trite analogy to oil, but here is the point: Preserving redundancy through a transition offers continuity of function, security, and a sense of comfort. People are loathe to get off their old paradigm before the new one has proven itself to offer full utility under all conditions. When it all happens seamlessly, it’s an orderly transition.

The end of oil?

Refrains about the ‘end of oil’ have been loud, especially over the past half-dozen years. More recently the chorus has also pushed the lyrics that natural gas is soon on its way out too. Singing from the same song book has instilled a belief that the consumption of fossil fuels is falling off as renewables rise to replace them.

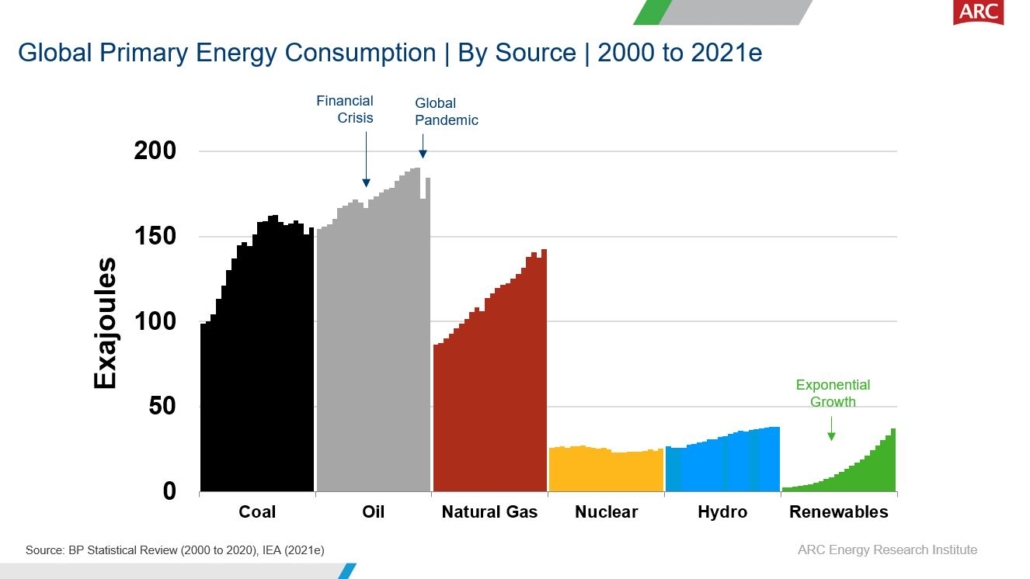

So, what does the updated data show? The global trends to 2021 are shown in the Figure below.

Post-pandemic resurgence in total, primary energy demand has been swift, reinforcing past trends as if the virus did nothing. Looking at individual energy sources, growth in coal seems arrested, but any decline is hardly convincing. Oil and gas continue to grow linearly. Hydro and nuclear power show modest growth.

Renewables — mostly wind, solar and biofuels — are demonstrating the most impressive growth, an exponential curve. Yet substitution, hence transition, is elusive. From a global perspective the world’s energy supplies are diversifying into renewables, not yet transitioning off the deeply entrenched fossil fuel paradigm.

In other words, renewables going up is not translating into oil and gas going down.

Confirmation bias

Attend any conference on the future of energy and you’re likely to see variations of charts that shows only growth in renewables and electric vehicles. Exclusion of oil and gas trends yields a confirmation bias that reinforces a belief that substitution of fossil fuels is happening when it’s not. Six years after the signing of the Paris agreement, progress towards energy transition has been glacially slow. Only a handful of countries can claim meaningful transition trends — the world as a collective has far to go.

Adopting incomplete views of what’s happening to confirm trends we want to be true, but are not true, is hardly productive toward achieving a goal like net-zero emissions by 2050.

In reality, after nearly 50 years since the first oil price shock in 1973, and the first cries of “we need to get off oil,” the world continues to demand more, year-after-year, punctuated only momentarily by events like the global financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic.

A needed crisis?

As energy prices spike, some are suggesting that the shock of higher fossil fuel prices and supply constraints are exactly the catalysts needed to accelerate the transition to clean energy systems. There is some merit to this argument.

The 1970s oil price shocks induced what I called a ‘breakpoint’ in my 2006 book, A Thousand Barrels a Second: The Coming Oil Breakpoint and the Challenges Facing an Energy Dependent World. Rapidly inflating prices and insecurity of supply triggered policies and actions to transition worldwide power markets. Nuclear fuels came in and substituted for burning oil in power plants — it was a real energy transition. But going nuclear didn’t happen without a lot of cost for relatively little change on the whole fossil fuel complex. The knock-on effects of energy inflation induced a lot of economic malaise and in the end only a small fraction of oil was displaced before demand came roaring back.

Today’s energy price volatility is not positive for transitioning away from fossil fuels. Society is in a precarious state at a personal level. Mindsets are fragile with a pandemic-weary populace that’s already angry and anxious.

Thinning wallets, queuing at gas stations and having to choose between a cold shower and a hot meal leads people to think about political change, not energy change. Someone who is throwing a fist in a petrol queue isn’t thinking about climate change and the role of hydrogen in a thirty-year plan. They’re thinking about getting through the queue, getting home and paying their crushing utility bills before 30 days at the end of the month.

Disorder that penetrates households can create civil unrest. At a minimum disorder breeds the blame game, with politicians the first target of discontent. Governments are already acquiescing to civilian pressures by subsidizing fuel prices, easing climate policies and naively reassuring people that they will get back to normal as soon as possible. Climate-unfriendly politicians are already strategizing how to take advantage of the situation in our democracies. They know this is hardly a time when people can be convinced to shoulder a new burden to limit carbon.

Disorder and distractions in government are damaging at a time when the transition to most clean energy systems are still heavily dependent on policies.

Giving up the ball

The rise of renewables between 2010 and 2020 will be recorded as one of the biggest events in energy history. But it wasn’t the biggest. Whether measured in Joules or dollars, the rise of U.S. shale gas and oil was a bigger transformation. American independent oil companies (IOCs) aggressively took global oil market share, so much so that for the first time in five decades the control of oil markets shifted from the OPEC cartel to greater free-market, global competition.

Market leverage held by Middle Eastern and Russian interests was suppressed as the phrase ‘energy dominance’ entered the American lexicon around 2014. Unfortunately, the possibility that western IOCs could tilt the balance of power in global oil markets was a short-lived notion.

Growing oil supply to meet demand requires ongoing investment. Since 2018 or so, western IOCs have been under increasing pressure from environmental groups, energy agencies and financial institutions to contract their investment and hold production flat. Arguments were made that oil production can’t be decarbonized, that the world won’t need more oil, and demand will collapse because of the transition to wind, solar and electric vehicles.

Unfortunately, nobody told the consumer to contract their petroleum consumption at the same rate as the producers. Nor did the realization sink in that, people like redundancy (like the security of a paper map) before they transition to something new, lest they feel lost and have to endure inconvenience and hardship.

The pandemic has been hard on all supply chains including oil and gas. Like IOCs, nationally-owned oil companies (NOCs) also reduced investment to adjust to the momentary fall in demand due to COVID-19. But the snubbing of western IOCs through divestment and other dismissive directives is exacerbating price volatility. Western market influence that was gained in the 2010s has been lost. We don’t need a lot of analysis to understand where we are at: It’s telling that the President of the United States now has to make calls to OPEC to stabilize the brewing energy crisis, instead of calling the CEOs of Western IOCs. Similarly, European leaders are now hostage to Russian natural gas interests.

Hackneyed advice

The notion of working with Western oil and gas companies to reduce emissions quickly and be part of an orderly transition to a clean energy future is anathema to those working hard on clean energy transformations and climate change policy. But animosities go even deeper. Non-emitting nuclear power is often left out of discussion too (did I mention that the price of uranium is up 45 per cent since the beginning of the year?)

As a side note, the grass isn’t greener on the clean side of the energy fence: Lithium prices for electric vehicle batteries are now at an all-time high and many vital minerals clean energy technologies are in short supply.

Everyone is tired of hearing the commoditized saying “never waste a good crisis,” especially as it seems we just go from one to another. At a minimum let’s avoid the ones that are made by human fallibilities, for example hearing only what we want to hear and being dismissive of complex geopolitical realities.

Reducing emissions as soon as possible will require orderly transition against a background of relative economic and social stability. It seems as idealistic as another hackneyed adage: “let’s all work together.”