Commentary – Oil’s School of Rock is Paying Off

Learning takes time and effort. But a good education pays off.

North America’s oil industry has been in school for the past three years, studying how to become more productive in a fragile $50-a-barrel world. Many companies in the class of 2017 have graduated and are now competing hard for a greater share of global barrels.

Having said that, North America’s education on how to make oilfields more productive appears to be stalling. After a breathtaking uphill sprint, productivity data from the US Energy Information Agency (EIA) shows that the last few thousand oil wells in top-class American plays may have hit a limit—at least for now.

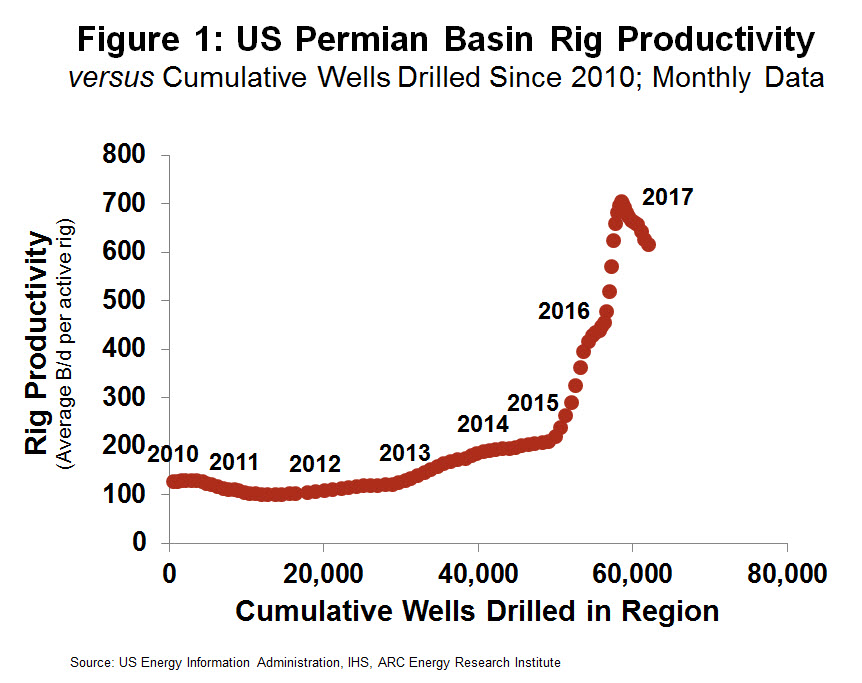

Our Figure this week shows a classic S-curve learning pattern in the mother lode of all oil plays: the Permian Basin. Slow improvements to rig productivity (2012 to 2015) were followed by a steep period of rapid learning (2015 to 2017). Eventually limitations set in and advancement quickly stalled upon mastering new processes (2017 to the present).

As with many things in life it’s repetition that leads to mastery. Getting to know the rocks better and using progressively better techniques to extract the hydrocarbons facilitate learning in the oil and gas business. Each subsequent well that’s drilled yields a better understanding on how to drill and extract the oil buried several kilometers beneath a prospector’s feet. Trial, error and breakthroughs through repetitive drilling have been a longstanding hallmark of this 150-year-old business.

As with many things in life it’s repetition that leads to mastery. Getting to know the rocks better and using progressively better techniques to extract the hydrocarbons facilitate learning in the oil and gas business. Each subsequent well that’s drilled yields a better understanding on how to drill and extract the oil buried several kilometers beneath a prospector’s feet. Trial, error and breakthroughs through repetitive drilling have been a longstanding hallmark of this 150-year-old business.

The “light tight oil” (LTO) revolution began in North America circa 2010. It took about 30,000 wells and three years before the learning in the Permian Basin kicked in. The next 20,000 wells yielded an impressive doubling of productivity. But it was innovation from the following 10,000 wells when mastery set in; by the time the 60 thousandth well was drilled the amount of new oil produced by a single drilling rig (averaged over a month) more than tripled to 700 B/d.

Aside from learning more about the rocks, the following six factors have contributed to the tight oil learning curve:

- Walking rigs – Assembling and dismantling rigs for each new well used to be an unproductive, time consuming process. Wrenches and bolts are passé; new rigs “walk” on large well pads needling holes in the ground like a sewing machine on a patch.

- Bigger, better gear – From drill bits to motors, pump and electronic sensors, all the gear on a rig is now more powerful and more precise.

- Longer lateral wells – A horizontal well is like a trough that gathers oil in the rock formation. Why stop at one kilometer when you can drill out two or three with the better gear?

- Fracturing with greater intensity – Hydraulic fracturing used to be a one-off, complicated process. Today, liberating tight oil is like unzipping a zipper down the length of a lateral well section.

- Smarter, better logistics – Idle time on well sites can cost tens of thousands of dollars an hour. Modern supply chain management and logistics are helping operators use every hour of the clock more cost effectively.

- ‘High grading’ of prospects – Low oil prices culled the industry’s spreadsheets of uneconomic play areas. Activity migrated to high quality ‘sweet spots’, which are turning out to be more plentiful than originally thought.

How much better can it all get?

The data in our chart, and from other plays, suggests that the collective learning from these factors may have peaked; ergo a high school conclusion might lead us to believe that the golden geese—tight oil wells drilled into prolific plays like the US Permian and Eagle Ford—may have finally finished laying bigger and bigger eggs.

But it’s not wise to be fooled into that sort of undergraduate thinking. Productivity may have stalled for now, but the learning is paying off. The rate of output growth in the new genre of light tight oil plays isn’t about to lose momentum around the $50/B mark.

Learning is infectious. And what good student starts from the proverbial “square one?” Only fools reinvent the wheel. Knowledge gained from American “tight oil” plays is spreading to other plays and has already spread north into Canada where conditions favour copycat learning. Plays like the Montney and Duvernay are already climbing up their learning curves.

All this learning sounds like bad news for oversupplied oil markets. Yet there is a flip side: The good news for North America is that not everyone is going to the same school. Those on the other side of the world aren’t drilling thousands of wells from which they can learn. They’re relying on OPEC valve closures to save their competitiveness in the old-school way of doing things.

The irony is that OPEC’s artificially supported oil price is tuition for North America’s industry. On their tab we’re learning how to produce more oil at cheaper prices.