Commentary – Sharpening Pencils for the Future of Oil

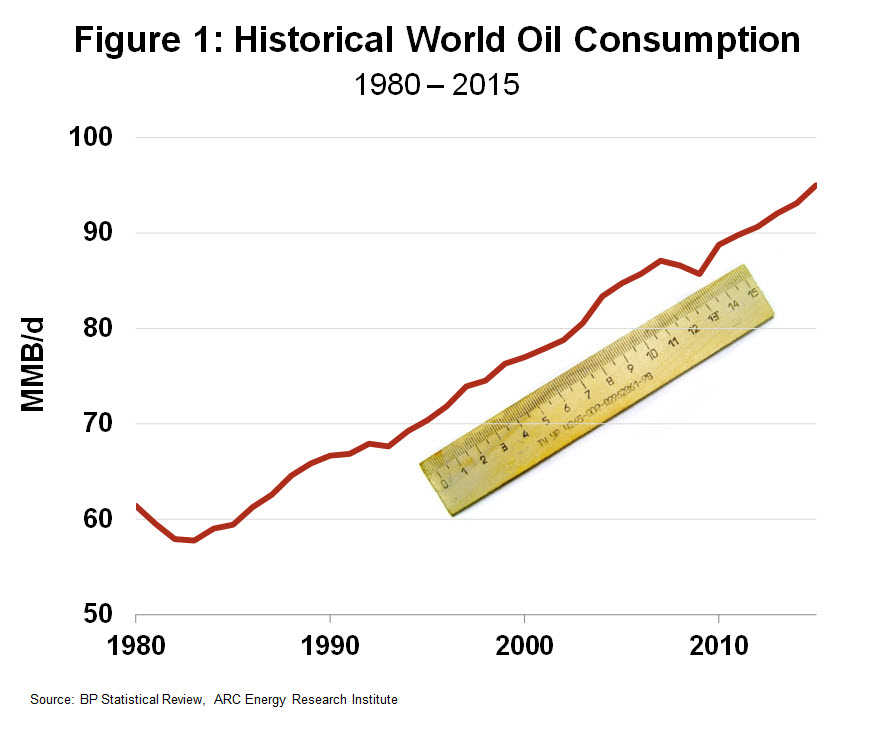

Get yourself a ruler, a pencil and a piece of paper. Place the ruler at about 45 degrees and draw a line upward across the page.

That’s what a chart of world oil consumption looks like over the past 30 years, give or take a few shakes off the line (Figure 1).

That was easy. Now think about how to draw oil consumption over the next three decades.

That was easy. Now think about how to draw oil consumption over the next three decades.

Plenty of pundits are scrubbing their spreadsheets and fidgeting with their rulers to show us the answer.

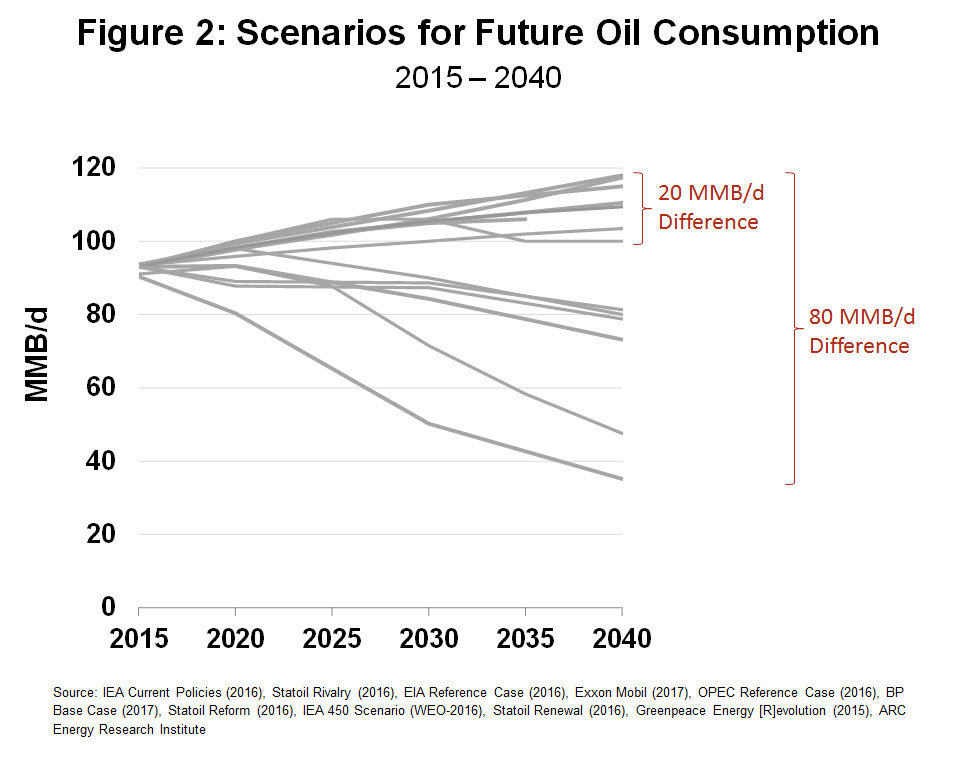

Some forecasters are economists who work for multinational oil and gas companies and government agencies. Most of their oil outlooks extend upward. The biggest uncertainty is the angle of their rulers.

The steepest slope assumes that our prevailing consumption habits and government policies are extended out a few more decades. Oil demand reaches nearly 120 MMB/d at the top of this cluster, up almost 25% from today. More moderate trajectories in the group are based on pledges made pursuant to the November 2015 Paris Climate Change Conference; but tallying up country commitments still suggests modest growth to between 100 and 105 MMB/d by 2040.

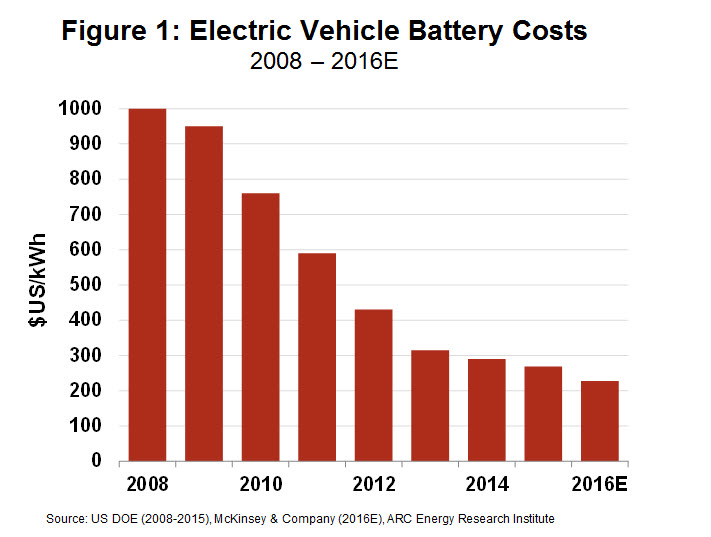

A group of weaker outlooks tilt downward like a loosely held hockey stick. Clustering between 73 and 80 MMB/d by 2040, this collection of prognostications assumes more aggressive global efforts to limit carbon loading in the atmosphere and the faster adoption of innovations like electric vehicles. The International Energy Agency’s 450 Scenario is the most bearish demand outlook among these peers.

Environmental groups don’t equate fossil energy usage to classroom instruments or clichéd sports equipment. Slick oil charts from naysayers with green-coloured glasses look more like a BASE jump gone badly. The most catastrophic scenario appears to come from Greenpeace, which proposes that pipelines will trickle in the range of 35 MMB/d by 2040.

What and whom to believe? The range of consumption estimates 25-years out is wider than the tailgate of a Ford F350; on one end is 35 MMB/d, on the other 120 MMB/d. Even the top cluster varies by 20%

What and whom to believe? The range of consumption estimates 25-years out is wider than the tailgate of a Ford F350; on one end is 35 MMB/d, on the other 120 MMB/d. Even the top cluster varies by 20%

Given the 80 MMB/d range in opinions and analyses (each convincing on their own), stakeholders in the oil business may feel a tendency to adopt a, “the truth lies in the middle,” forecast. This method instructs us to believe a midpoint somewhere between denial and exuberance.

Taking the median of all expert opinions and calling it the “consensus” of wisdom suggests oil demand will drop by 20% over the next quarter century. I don’t find this approach satisfying. Looking through a row of ten cloudy crystal balls doesn’t yield a new one of greater clarity.

For over 100 years, the oil industry and its stakeholders have believed that the market for their products will continue to grow ad infinitum without competitive challenges. Today, that thesis is about as useful as a bent ruler and a broken pencil.

Never in my 35-year career following energy markets has there been so much widespread disagreement about future demand for oil. And it’s a relatively recent confusion, one that’s been emerging over the past decade, but heightened in the past couple of years due to the potential forces of technological change and carbon regulation.

An 80 MMB/d disagreement in various outlooks says to me that there is little value to add by uploading yet another spreadsheet into an already foggy cloud of forecast charts.

I’m only confident in one fact and one forecast.

Fact: There is widespread ambiguity in expert outlooks for oil consumption, one of the world’s most vital commodities.

Forecast: The uncertainty is not going to diminish over the next five years at least. In other words, trends in technology, policy, economy and social factors are going to put wider and wider error bars on every pundit’s numbers.

In my mind, the fuzzy question of, “How much oil is the world going to consume by 2030 and beyond?” must now yield to sharper, qualitative thinking.

Pencils and rulers down, the questions going forward are, “What type of decisions will be made—relating to investment, corporate strategy, government policy and so on—under unprecedented uncertainty, and how will these near-term decisions affect the world’s long-term energy future?”

I’ll be pondering answers to these questions during my commute to work and back – in my new electric vehicle.

To be continued…

Source: Pixabay.com

Source: Pixabay.com