Commentary – The Biggest Transition Ever: How Big is Big?

Change in the world of wheels is accelerating! Momentum is building and some days it’s hard to keep up.

Every week, the assumptions about the future of transportation, and the energy systems that turn our wheels, are becoming more Jetson-esque.

The excitement is palpable and as a technology junkie I love it. Auto shows are rolling out new electric vehicle (EV) models; China says it’s planning on banning internal combustion engines (ICE); and Daimler is jockeying with Tesla in the budding electric truck segment. In the battery world, lithium prices have reached an all-time high on anticipated demand growth. In tow with all the EV news, there is a trailer full of autonomous vehicle talk that makes me think that 1950s Popular Science articles were real after all.

But it’s time to take our foot of the accelerator and make sense of it all.

For the next several columns I’ll be looking at what the pundits are saying, characterizing and examining all assumptions, and putting things into pragmatic context.

I know one thing for sure: this is a very complicated and contentious subject. There are no easy parallels. An electric car is not like a smartphone or a Netflix subscription. For one thing, neither had much competitive resistance.

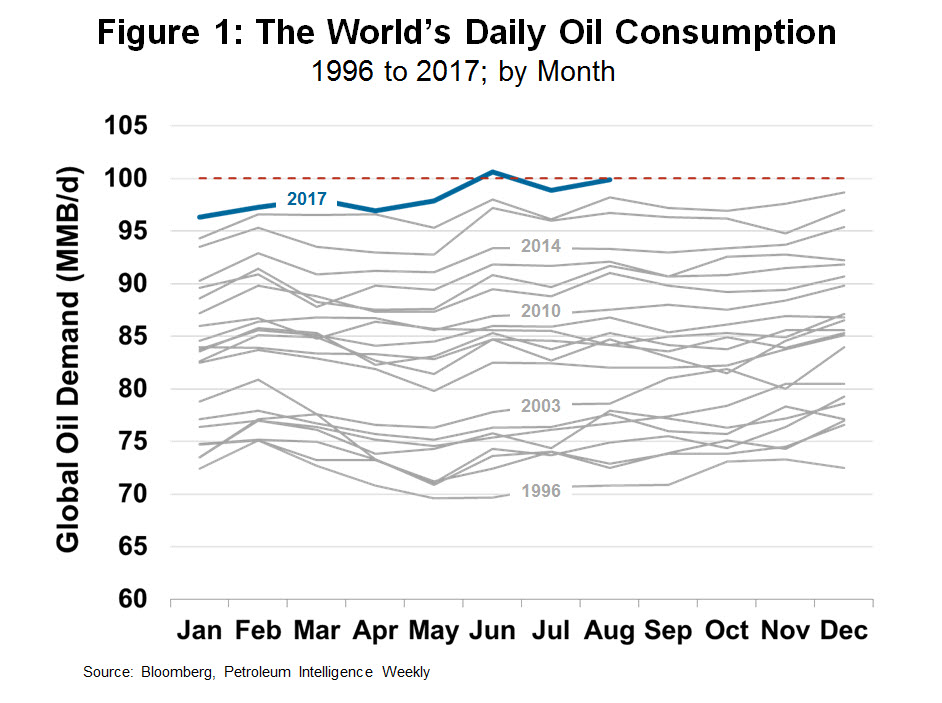

Parrying against the sunny alt-transport news, there is a cloudy, competitive reality. Global oil demand is ratcheting up at near-record pace. A couple of weeks ago, the International Energy Agency put our oil-addicted world on track for a 1.6 MMB/d of growth this year over last (the 20-year average is 1.2 MMB/d per year).

For 2018, analysts are already starting to escalate their oil growth forecasts. The lesson shouldn’t be lost on any of us: Never underestimate the consumer’s ability to overindulge in cheap energy commodities.

“Death of the Combustion Engine” and the “End of Oil” headlines are increasing in frequency on the promise of better, cheaper EVs with greater selection. Yet the actual data trends for ICE car sales and oil consumption are like pistons firing in the other direction, revving harder and racing away from any speculative eulogies.

What to believe?

There is little debate in my mind that big changes are forthcoming to our energy systems and transportation paradigms. For context, let’s think about how big is big?

The Biggest Transition Ever

Just the scale of what’s in play will challenge many assumptions and forecasts. As the baseball philosopher Yogi Berra once said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.”

When it comes to oil and autos, big is a word that is not big enough. Transitioning not one, but two of the largest industries in the world simultaneously is unprecedented. Both have multi-trillion-dollar roots as tough as oak trees.

Our daily dose of oil momentarily touched 100 million-barrels-a-day in June. I estimate we’ll sustain past that incomprehensible century marker by the middle of 2018. That’s the equivalent rate of burning an ultra-large supertanker of oil every half hour.

From a sales perspective, the top 10 integrated oil and gas companies recorded annual revenue in excess of $US 3.1 trillion per year in 2015. For comparison, the top 10 technology companies add up to $US 1.3 trillion in sales and they sell a lot more than just smartphones.

From a sales perspective, the top 10 integrated oil and gas companies recorded annual revenue in excess of $US 3.1 trillion per year in 2015. For comparison, the top 10 technology companies add up to $US 1.3 trillion in sales and they sell a lot more than just smartphones.

There are over 1.2 billion ICE-powered vehicles on the road today. If the average vehicle is modestly worth $US 20,000, that represents a potential fleet turnover of $US 20 trillion. Electrifying this fleet on a fast track won’t be limited by technology (it never is). Aggressive adoption scenarios will be a function of many other considerations; for example, who will compensate car owners for trillions of dollars of devalued capital stock?

And the capital stock of a billion-plus vehicles isn’t static. After scrapping 40 million clunkers every year, the overall vehicle fleet is still expanding at a rate of 50 million vehicles annually, 99 percent of which are still ICE-powered. Like oil, autos are big business too: Off the assembly lines, the top 10 conventional automakers generate $US 1.6 trillion in sales worldwide.

Oil and gas plus conventional vehicle sales adds up to more than $US 5 trillion per year of business. That’s a big tree to shake. The multi-trillion-dollar scale of what’s in play is unlike any other we’ve seen. So, even modest shifts in the way we turn our wheels will be hugely impactful.

Many unknowns are in play. Will the world be driving 1.5 or over 2.0 billion vehicles by 2040? How many kilometers will each person be traveling, on average? At what rate will people switch from ICE to EV? Will EVs be full or partial substitutes for each of the various wheeled transportation segments? What will the value of a used car be?

Change one small assumption in the decades to follow—for example, how long people hold onto cars before trading them in—and the forecasts are out by a couple hundred million electric vehicles, several million barrels of oil per day, and hundreds of millions of tons of carbon per year.

Next up: The assumptions behind the assumptions.