Commentary – OPEC Deals Send the Wrong Message: Closing Valves is not Innovation

OPEC and its cartel of friends must be sweating condensates in advance of their May 25th meeting.

The oil price war, triggered almost three years ago, is far from over. Calling a truce with production cuts has been an ineffective strategy. In fact, it’s been a feeble strategy and nobody in the business should rely on its extension to be effective.

Price wars are often triggered by the arrival of a new entrant into an entrenched market clique.

American light tight oil began flowing into petroleum supply chains in 2010. By 2014, output from plays like the Bakken, Eagle Ford and Permian had penetrated 4% of the world’s oil market, antagonizing starched interests in the industry.

There is a standard script for price wars that is played out in many businesses, not just oil. Airlines, pizza parlours and makers of high-tech equipment know the story line well.

Act I is the arrival of an antagonist, a new actor who tries to steal business from the old.

In Act II the leading defenders of market share lower their prices, flooding the market with cheap supply. The intent is to flush out the newcomer. Weak competitors are targets too.

By Act III all participants are overproducing to salvage market share. Prices collapse before intermission.

Tension peaks in Act IV as bankruptcy and distress claims high cost producers. The denouement takes place in Act V when surviving participants capitulate and the market returns to balance. Survival is predicated on financial strength, innovation and reducing costs.

Curtains close on Act VI, by which time long-term pricing returns to the market (often at lower price points than before the price war).

In today’s oil drama the resilience of many actors in Act IV (Bankruptcy and Distress) has been surprising. Producers like China, Mexico and Venezuela have seen their output decline due to underinvestment. But the declines have not been broad based; others have risen. Overall capacity shrinkage has not been fast enough to end the Act.

Act V was supposed to be when everyone capitulated. Surprise: Instead of being flushed out by lower prices, North American producers have been aggressively increasing productivity and driving down their costs.

The 2016 OPEC deal propped up prices, which was a gift to US and Canadian producers to keep going up the learning curve. While hard data is not all available yet, the EIA estimates that US rig productivities in major tight oil plays have increased by over 7% in the past six months, Canada’s operators are making similar gains.

OPEC’s issue—and other actors who are relying on OPEC for reprieve—is that the cartel is not following the correct script for ending a price war. Contrived “supply management” is not effective against a challenger that is bulldozing into the market with relentless innovation.

The appropriate defense against an innovative competitor is to innovate even faster.

In fighting a price war, closing a valve is not high up on the scale of innovation.

Tooling up to use the latest sub-surface processes and applying digital technologies is the future of low cost oil extraction. That’s what leading producers in the US and Canada are doing. And it’s why another OPEC deal is a fruitless strategy that merely extends Act IV: the demise of the inefficient.

Producers who are hiding behind a curtain of OPEC cuts are getting a misguided message. The implied narrative is, “Don’t worry, there is no need to improve your business practices and lower your costs through innovation. Everything will return to the good ol’ days once our supply cuts clear out the excess inventories of oil.”

On May 25th, oil markets are expecting that the OPEC-and-friends cartel will extend their supply quotas. And they likely will. However, the proper script would be to abandon the strategy of output cuts and let the market naturally choke off investment to the inefficient. Act IV can then play out faster, causing the production declines of high-cost defenders to set in faster.

Oil producers that follow the proper script of a price war will stay in business well after the curtains close. Those who don’t will die on stage from the sword of innovation.

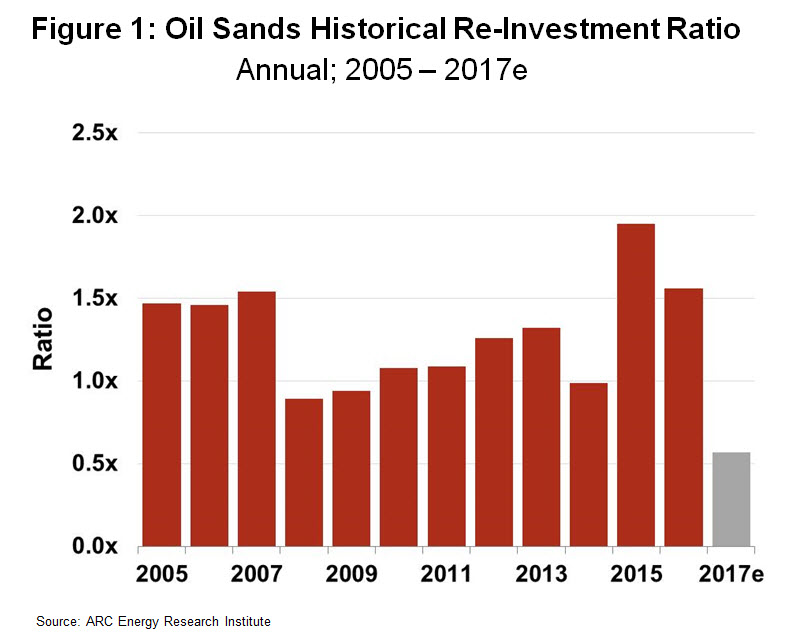

While growth capital for the oil sands region is on hold for the foreseeable future, the investment behaviour in the rest of Western Canada’s oil and gas business validates the appeal of our light oils, liquids and natural gas. Plays like the Montney in West Central Alberta and Northeast BC are showing very well. Capital investment outside the oil sands region is expected to be over $C 29 billion this year, a 40% gain over last. An expected re-investment ratio of 140% is a solid affirmation that the same technologies and processes that are making the plays like the Permian Basin famous are also delivering favourable returns in Canada at $US 50/B.

While growth capital for the oil sands region is on hold for the foreseeable future, the investment behaviour in the rest of Western Canada’s oil and gas business validates the appeal of our light oils, liquids and natural gas. Plays like the Montney in West Central Alberta and Northeast BC are showing very well. Capital investment outside the oil sands region is expected to be over $C 29 billion this year, a 40% gain over last. An expected re-investment ratio of 140% is a solid affirmation that the same technologies and processes that are making the plays like the Permian Basin famous are also delivering favourable returns in Canada at $US 50/B.